The Flowering of Color Printing

In “The Artist’s Garden: American Impressionism and the Garden Movement, 1887–1920”—the exhibition on view in The Huntington’s MaryLou and George Boone Gallery through May 9—you can catch a glimpse of a 19th-century innovation that brightened the visual culture of the age: color lithography, or stone printing in multiple inks.

Examples of this process fill a display case and hang on a gallery wall, framed and protected like priceless masterpieces. They include color plates from mail-order seed catalogs and pocket-size promotions called trade cards that were intended to stimulate sales with eye-catching images. These minor, transient documents of everyday life, known as ephemera, became works of art in their own right thanks to a little inventiveness.

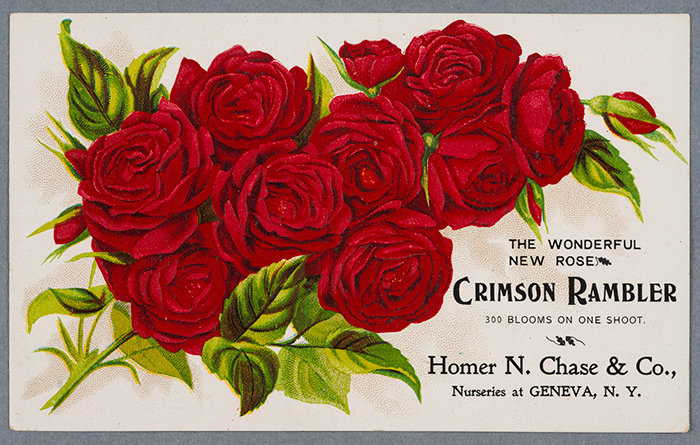

Of the tens of thousands of colorful trade cards printed by 1900, those made to promote nursery and seed companies are among the richest sources of color lithography. The process boosted an industry whose sales relied on vivid illustrations to capitalize on the American garden movement. The Wonderful New Rose Crimson Rambler, trade card, ca. 1900, Vredenburg & Co. Rochester NY, color lithograph on paper, 3½” x 5¾”. Gift of Jay T. Last. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Americans of the 19th century came to live in a world bursting with color, made possible when a young German playwright named Alois Senefelder (1771–1834) developed a new printmaking process called lithography in the 1790s. Lithography enabled Senefelder to make more copies of his plays in less time and for less money than ever before. Little did he know that his discovery would also start a marketing revolution far from home.

Lithography “colorized” America as newly affordable images in a rainbow of hues came to almost every community and home by the 1870s: advertising posters filled store windows, product labels on packaged goods lined display shelves, event signage blanketed buildings, and scenic prints decorated the walls of Victorian sitting rooms. The process became so universal that Americans saw color lithographs from the moment they woke up until the time they went to bed.

Into this new world of color entered another marketing marvel. At the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, manufacturers from around the world showcased technological innovations of all kinds—including the telephone and typewriter. The entrepreneurial spirit behind the Exposition also spurred the widespread use of lithographed trade cards to advertise these new goods and services.

Color plate illustrations depicting fruit and floral varieties populated mail-order seed catalogs and horticulture magazines of the period. Their characteristically bold, vivid designs practically jumped off pages otherwise filled with black-and-white text. This example appeared in a publication circulated by The Dingee & Conard Company of West Grove, Pennsylvania. The “Duchess Collection” of New Cannas, color plate illustration, ca. 1897, H. M. Wall, Brooklyn NY, color lithograph on paper, 9½” x 6½”. Gift of Jay T. Last. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Printers such as Louis Prang of Boston and Clay & Richmond of Buffalo began making color-lithographed trade cards in the early 1870s. Production soared in 1876 to meet America’s demand for quick, low-cost, high-volume advertising. By the 1880s, trade cards formed a major segment of the printing industry as lithographic firms from coast to coast boomed with activity. Cards were distributed at stores, mailed inside product boxes, dispensed by traveling salesmen, given away at exhibit booths, hawked by advertising agents, and handed out by children on sidewalks.

Lithographers printed two types of trade cards: custom and stock. Custom cards were made to order, featuring designs commissioned by manufacturers or retailers. They were among the earliest attempts to build a brand by using imagery, logos, and catchy slogans to promote quality, evoke trust, and ultimately to create product loyalty.

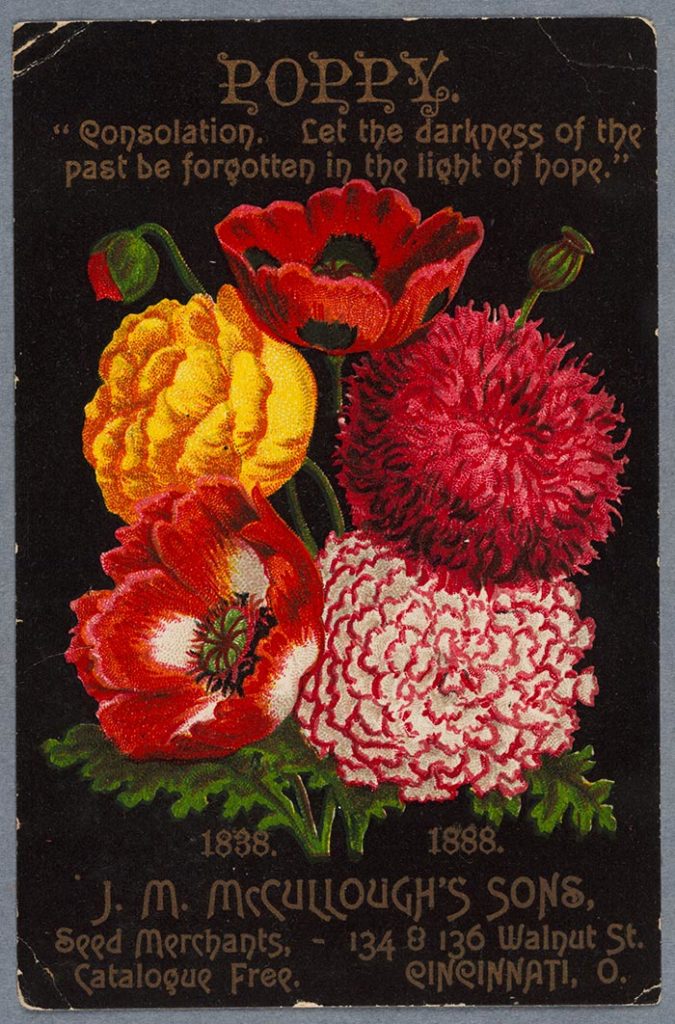

Cincinnati seed merchants J. M. McCullough’s Sons issued this stock trade card in 1888 to promote its latest selection of bulb varieties, and to celebrate 50 years of business. The company’s name, location, and significant dates are overprinted on the front. Text printed on back reminded the customer that “Holland bulbs and flower roots” were available for “Fall planting, Winter and Spring blooming. Now is the time to Plant! Call at the store or send for our beautifully illustrated catalog, free.” Poppy, trade card, 1888, unidentified printer, color lithograph on paper, 4¾” x 3”. Gift of Jay T. Last. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Stock cards were low-cost alternatives for budget-conscious promoters. They rolled off the presses almost ready-made: generic images personalized with a vendor’s name and address. The information either filled designated spaces on the card or was layered over the design.

Both types of cards employed colorful images on the front that often helped consumers picture the product and know what to expect. Sometimes, however, the image did not directly relate to the product, so the real sales pitch came from product descriptions on the back, complete with testimonials, ordering details, and occasional boastful claims.

Lithographed trade cards declined in popularity in the 1890s as nationally circulated magazines and local newspapers became the advertising medium of choice, but not before tens of thousands of the cards had populated America’s consumer culture, introducing buyers to a product market of unprecedented variety and quantity.

Even eye-catching trade cards like these were created for temporary use and expected to be discarded. However, the combination of attractive images printed in full color and a clever marketing strategy to issue cards in sets made them irresistible to collect and save. Mignonette, Dahlia, Phlox, trade cards, 1888, unidentified printer, color lithograph on paper, 4¾” x 3”. Gift of Jay T. Last. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

And although stone lithography gradually faded from commercial use after 1900 as photographic techniques replaced skilled handwork and metal printing plates supplanted stone, the techniques of lithography live on. Lithography employing metal and rubber plates is used for almost all high-volume commercial printing today, and stone lithography persists as a preferred printing method in fine art studios around the globe. The world of color created by Senefelder’s invention is still the world in which we live.

The exhibition catalog, The Artist’s Garden: American Impressionism and the Garden Movement, is available from the Huntington Store.

David Mihaly is the Jay T. Last Curator of Graphic Arts and Social History at The Huntington.