Take Me Out to the Ballgame with A Trade Card

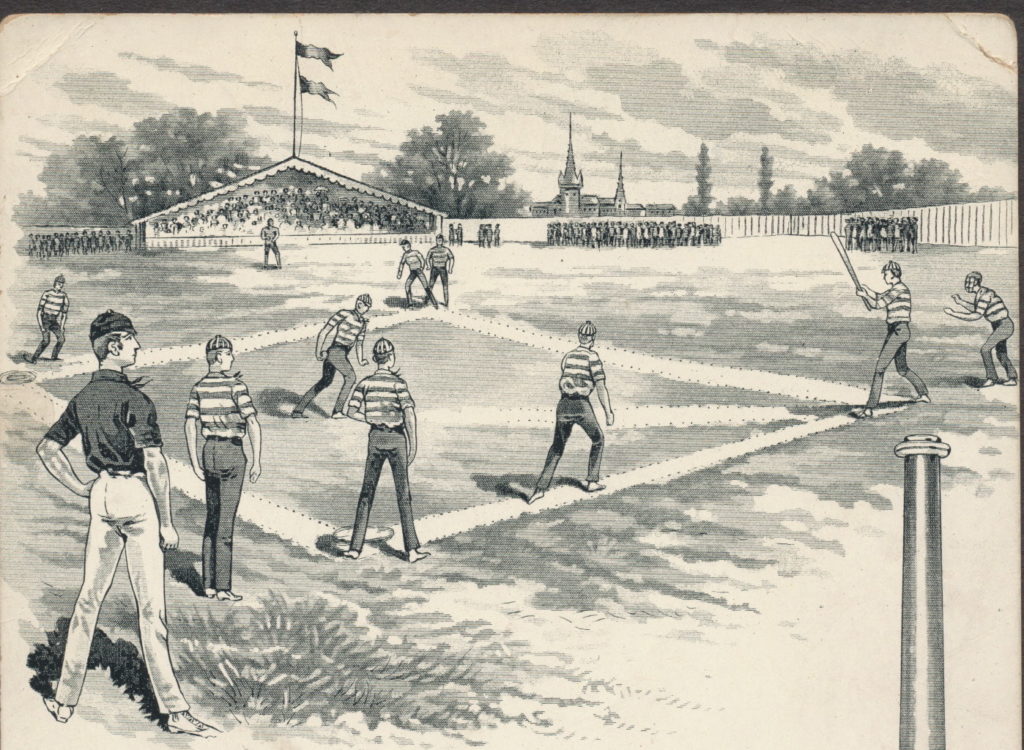

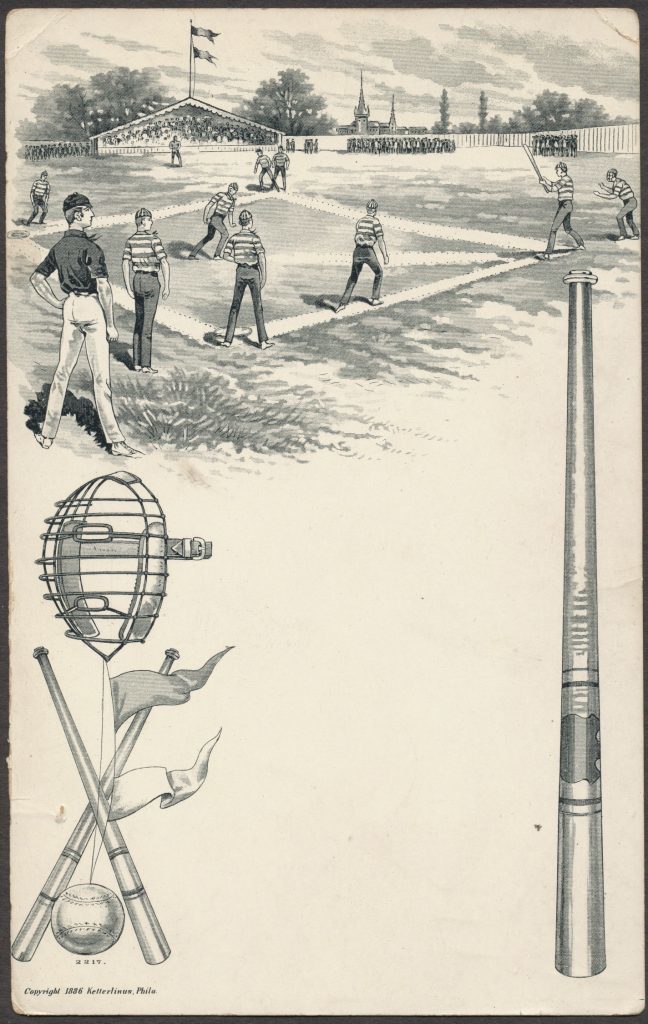

This 1886 trade card (4 3/8” X 7 3/8”) depicts a baseball game and reproduces equipment that appears dated to contemporary viewers. Yet despite its antiquity, we recognize the images, affirming that the basic game of baseball has not changed in the 130 years since the card was issued.

The card was produced by Ketterlinus Printing, a distinguished Philadelphia printing and lithography business founded by brothers Eugene and Paul Ketterlinus (1842). Eugene’s son, John Louis, acquired the company in 1876 and under his direction, Ketterlinus Lithographic Manufacturing Company prospered and grew until it closed in 1970. The baseball images on the card (#2217) were most likely standard sports subjects available to customers. Since there is no business name printed on the card (it would have appeared in the blank space between the balls/bat/mask on the left and the vertical bat on the right), and the back is blank, this example may be a salesman’s sample.

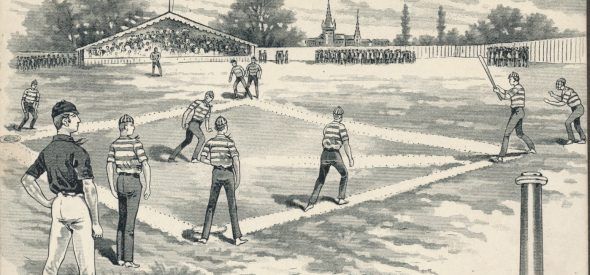

Baseball was America’s premier sport in 1886 and game depictions were a popular subject for trade cards since they reproduced details that were familiar to late nineteenth century cranks (fans). For example, none of the players wear gloves. Gloves were introduced around 1875 but, because they were thought to be unmanly, did not become popular until 1895.

The pitcher delivers the ball underhand. Side-arm delivery was allowed in 1883, and the over-hand delivery was permitted in 1885. But the underhand delivery was the established style in 1886.

Umpires have long been the object of fan and player ire, and hardly a game was played in the nineteenth century that didn’t feature a dispute with an umpire. Until 1879, when a second umpire might be added for an important game, there was only one, positioned behind the catcher, and he kept track of all the pitches and the action on the field. In this card, the second umpire is positioned behind the runner at third, while the home plate umpire is not shown.

The stadium looks familiar—there is a grandstand and the playing field is enclosed by a fence. However, there are two groups of people standing in right field, directly in the line of play. These fans bought general admission tickets and it was a common practice in the nineteenth century for them to stand in the outfield, or at a remove from the base-paths. If a fly-ball were hit to the outfield, the crowd was expected to move and allow the fielder to catch it. In some instances, though, fans might interfere with a ball hit by an opposing player, or they might obscure the fielder from catching a ball hit by the home team. An umpire’s lot was not a happy one at these moments of home team chicanery.

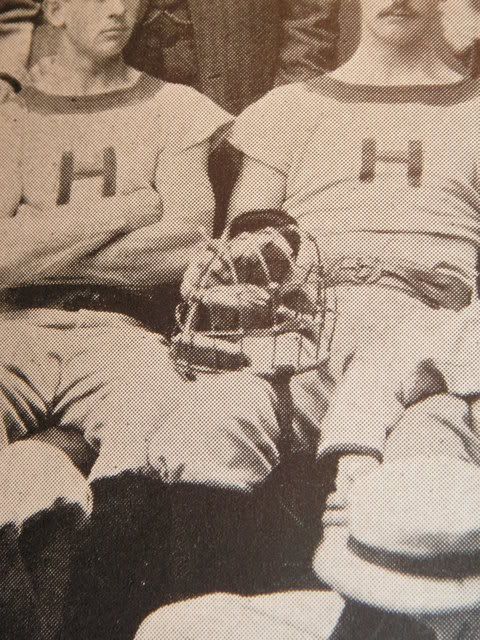

A catcher’s masks was first worn in 1877 by Harvard’s James Tyng . Tyng’s manager, Fred Thayer, modified a fencing mask for the first version, later developing and patenting the bird-cage mask shown here.

The bat on the card is a unique version of the wagon-tongue model which featured a flat barrelhead (not rounded) and a two-tiered flat knob at the end of the grip. Like many nineteenth-century bats, it has two rings with the manufacturer’s label positioned between the rings, characteristics of the ring-bat.

One of the enduring attractions of baseball is that the basic game has not changed much since the end of the Civil War. That is why a twenty-first-century viewer immediately recognizes a baseball game and equipment on the Ketterlinus trade card. By looking closely at the depicted images, we discover more about the roots of the game, and we take a step back in time to witness an 1886 version of the National Pastime.

Michael Peich, a devoted baseball fan, historian, and vintage card and ephemera collector, is Emeritus Professor of English at West Chester University. His website devoted to early 20th century Southern minor league baseball cards can be found at https://t209-contenetnea.com. A member of the Ephemera Society of America, he serves on the ESA Conference Planning Committee.