Swiss Communications Calculation

On the eve of the Great War, in 1914, a clever Swiss businessman invented and manufactured a “Posttaxenschieber” — an ingenious sliding scale that could calculate the cost of every form of communication available. The device was patented, was available at Huber’s shop on Tödistrasse in Zurich, and cost two and a half Swiss francs. The franc was similar to our dollar and was divided into 100 rappen, or centimes.

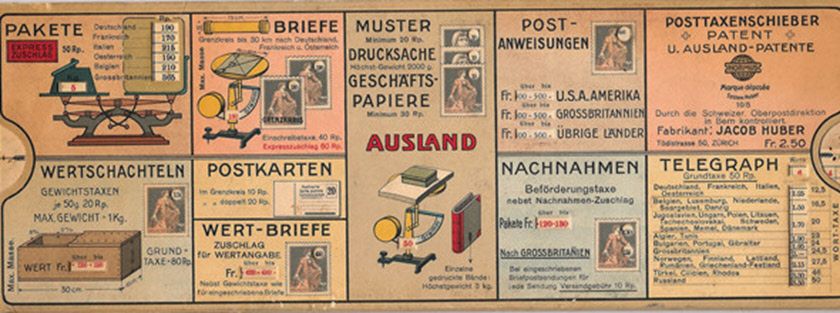

On one side, the scale covered the information for internal use in Switzerland. The ten illustrated panels showed, in the little square openings, what you would have to pay to: send a heavy express package, a lighter parcel, an ordinary letter, an express letter, a postcard, a money order, and insurance on any of the above. The postage stamps pictured were from two series. One, first appearing in 1907 but current until 1925 included the image of William Tell’s son with his crossbow for a small denomination, and the female warrior Helvetia with her sword for higher denominations. The second series had just been introduced in 1914 and showed the head of William Tell.

The calculator also showed (two panels on the right) how much a telegram would cost (60 rappen fee plus words at 5 rappen each, or 110 rappen for a 10-word telegram). And how much a telephone call would cost — a minimum of 10 rappen for 3 minutes. The fact that postal rates appeared together with these electric communicators distinguishes Switzerland (and, indeed, the rest of European countries) from the United States where, despite decades of discussion beginning in the 1840s, the Post Office Department failed to get Congressional approval for absorbing the telegraph. Only in America were electromagnetic communications solidly (and still) in the hands of private enterprise.

On the other side of the calculator are the various rates for foreign communications. Again, prices are shown for different classes of packages, and letter mail, and postcards. For France, Austria, and Germany it is pointed out that, because of the pneumatic tubes, there is a diameter limit to mail of 10 centimeters. In addition to mail, you could send a telegram to Great Britain, but not to the United States (presumably, you could direct onward transmission via cable from one of the intermediate places).

Significantly, there is no long-distance telephone — as there was not, really, in the United States. Although there was a line connecting New York and Chicago in 1892, and then to Denver in 1911, ordinary citizens did not avail themselves of a very costly service that kept snagging on the limits of sound transmitting technology. Finally, in 1914 a transcontinental telephone call was possible but was not accomplished until Alexander Graham Bell ceremoniously placed the first call from New York to San Francisco in January 1915. That first call involved several operators and took almost a half-hour to connect — but those of us old enough to remember service just post World War II know that long-distance calls remained expensive and exotic for a long time.