Larkin – The New Business Model

In this post, Dick Sheaff presents ephemera that points to a new business model – selling by mail. You don’t actually go to the target market yourself – you mail to it. An example of that model is The Larkin Company of Buffalo, which fine-tuned the model to a highly successful level. I guess that’s why I like to buy good examples of their marketing ephemera whenever I see them.

We’ve seen ‘Western’ films with the Medicine Salesman driving his wagon from town to town to sell his magical medical products (normally containing liberal quantities of alcohol) at the end of a Medicine Show. That’s very inefficient but it was the accepted way to market to those rural markets in the mid-to-late 1800s.

The model was simple – sell soaps by mail to agents who would take orders from their neighbors and friends. As well, incentivize it so that they were highly motivated to recruit other buyers. (I would note that this model was not unknown even recently to manufacturers of cosmetics and other products.)

With Larkin’s soap, they were selling convenience – for a price. Instead of making her own soap the housewife could free up some of her time by purchasing bars of soap from Larkin. And she could receive premiums by recruiting her friends to purchase fixed dollar amounts of soaps and an array of other Larkin products every month. Hey, what’s better than convenience at no net cost?

And it all began in 1875 when John Larkin launched his own soap company in Buffalo. His brother-in-law, Elbert Hubbard, provided the sales savvy. Not long after they were joined by a very young Darwin Martin, their first office person. They made a lot of money in the last part of the 1800s, to the extent that the company hired Frank Lloyd Wright to design the Larkin Administration Building in Buffalo in 1904. And Darwin Martin hired him to design the Darwin Martin House, which still stands. Larkin was a serious business generating serious money.

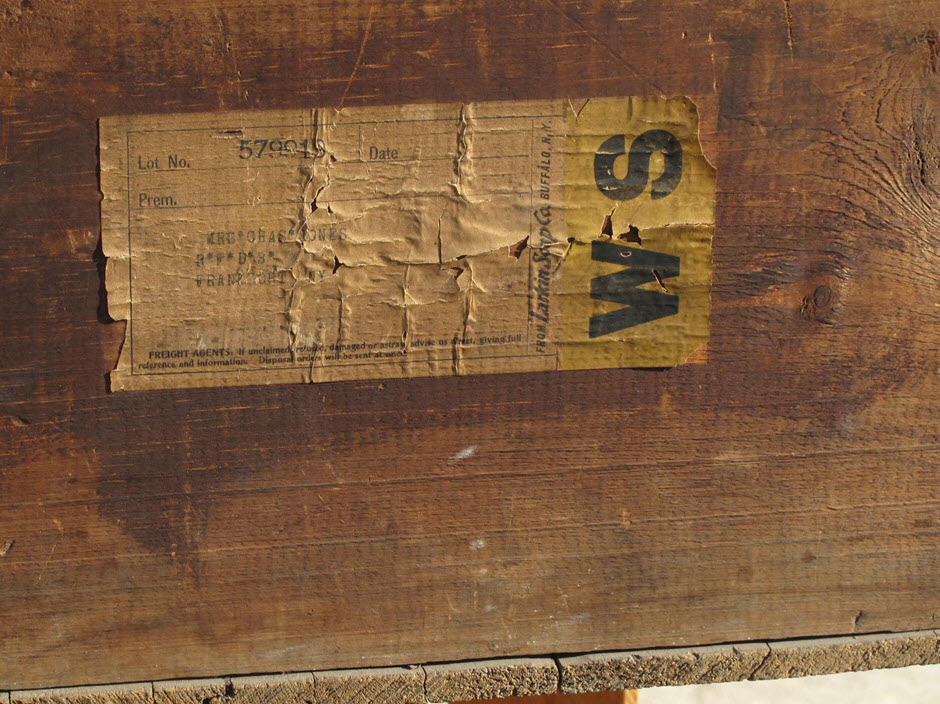

At the Madison-Bouckville Antique Week this past August, I spotted the type of box in which those money-spinning quantities of soap were shipped (Figure 1). It even had the original shipping label attached (Figure 2).

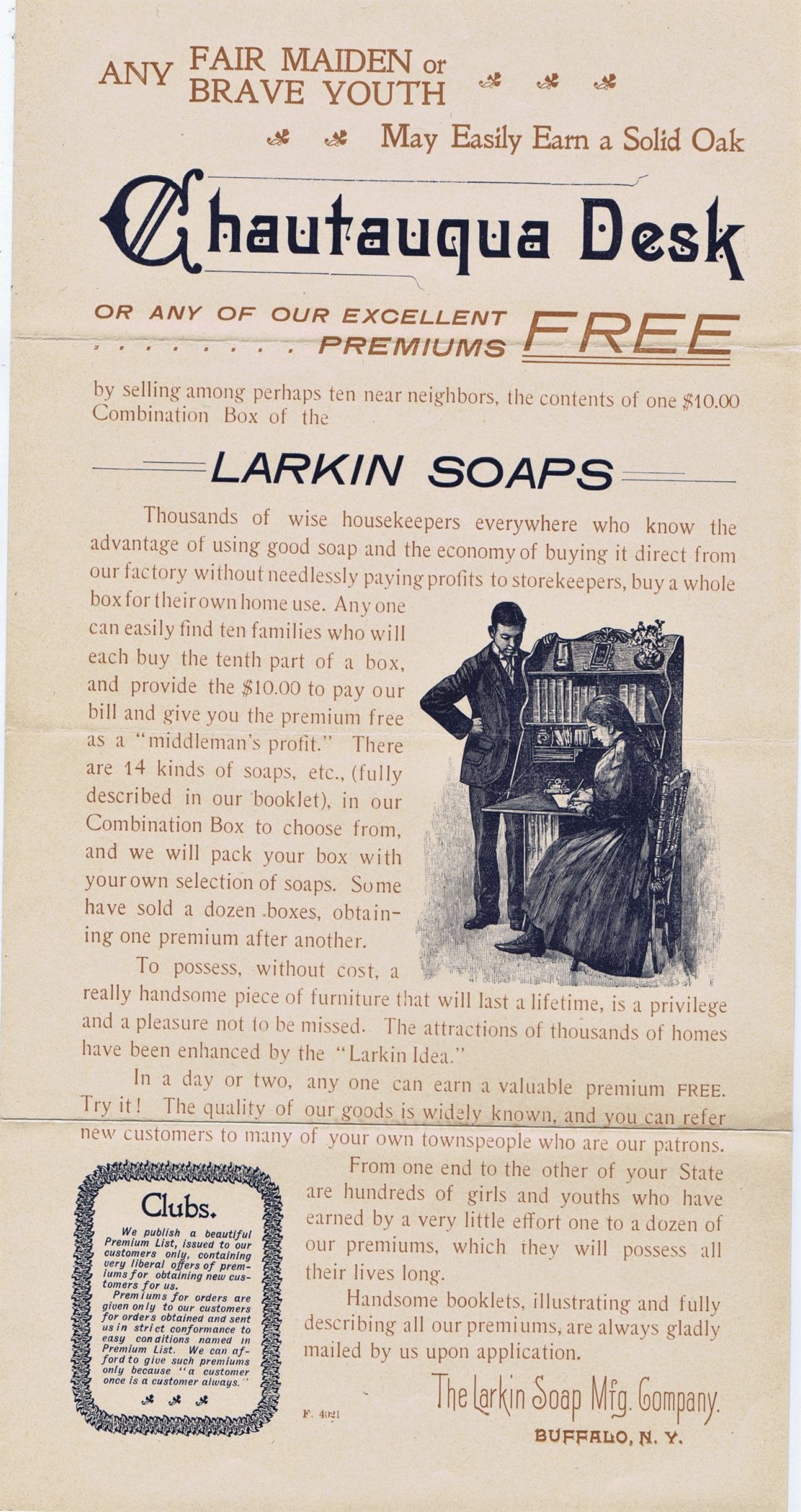

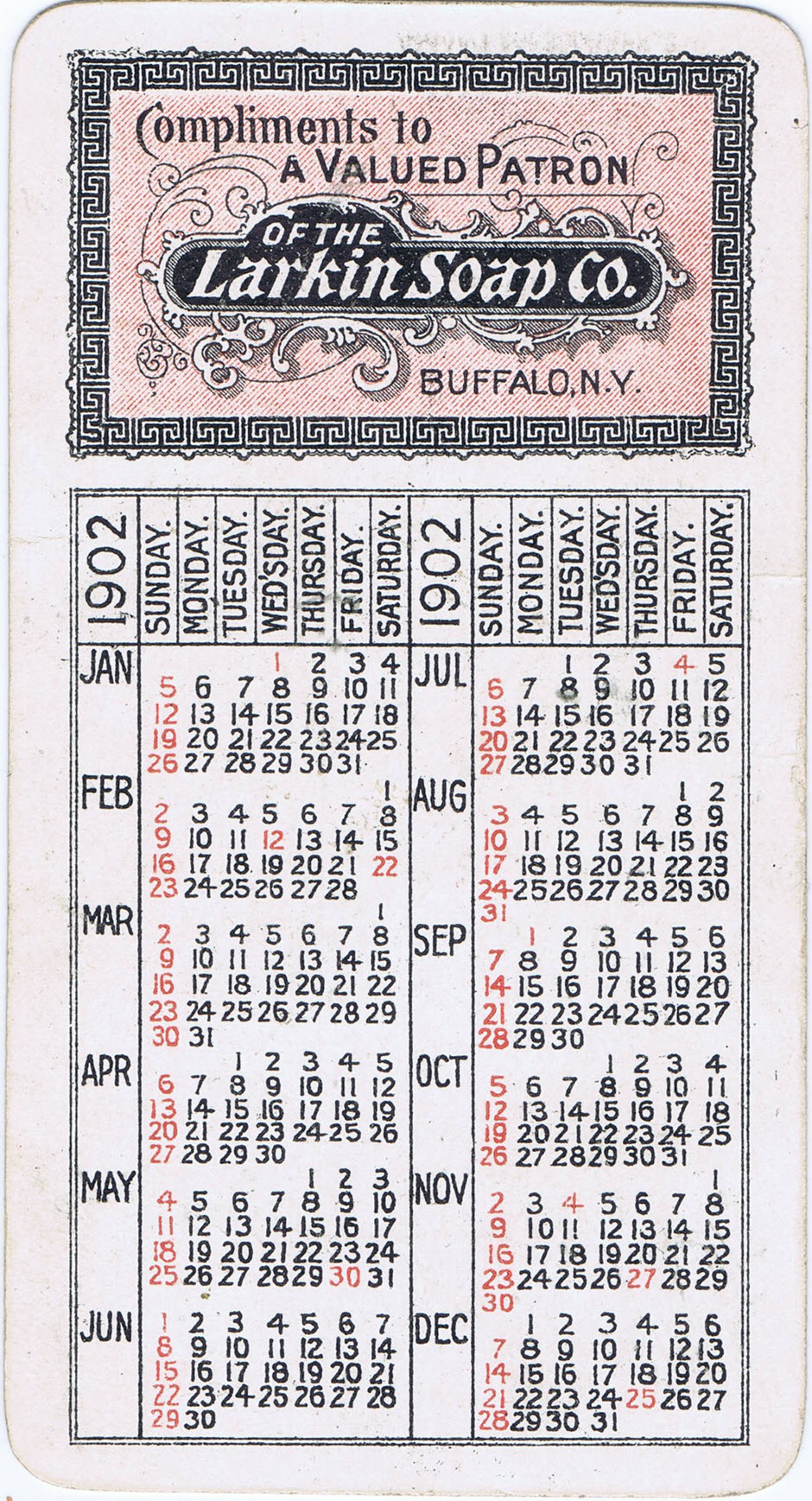

One of the keys to the success of the business was premiums. Reportedly one of the most popular ‘freebies’ was the Chautauqua Desk pictured in Figure 3. But there were more than desks. Even the basic pocket calendar was used to promote the company (Figure 4).

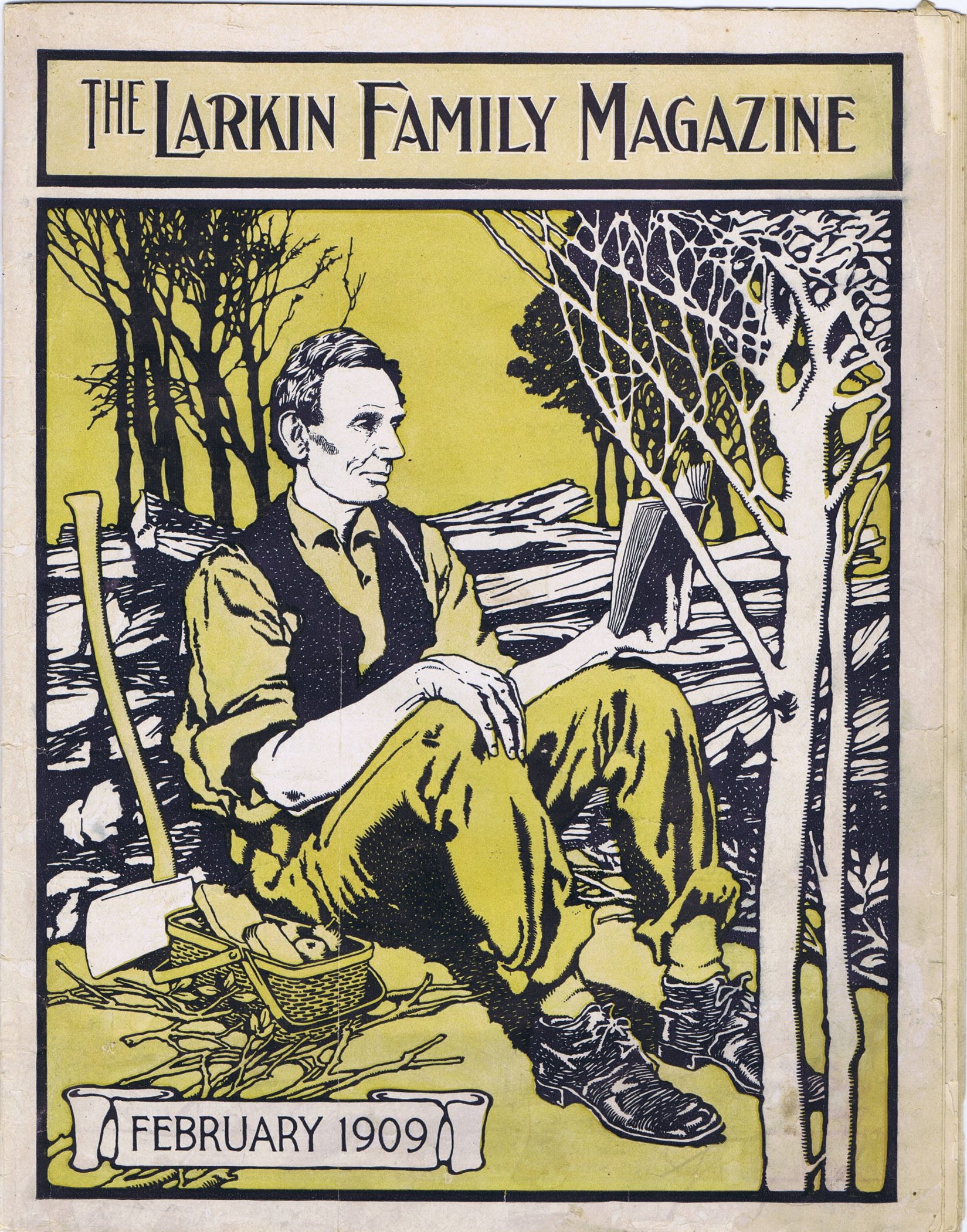

A corporate magazine, as per the 1909 example illustrated in Figure 5, “The Larkin Family Magazine”, contained articles such as a well-illustrated report on the Company’s booth at the New England Food Fair in Boston in 1908, as well as patterns and other useful household information.

Even the title reflects a degree of marketing genius – it’s a ‘family’ magazine in terms of its contents, but it’s sent to the ‘Larkin Family’ of salespeople. You weren’t just a member of your own local family at home – you were also a member of the vast ‘Larkin Family’ across America. And the cover, showing ‘Honest Abe’, associated the company with honesty and integrity.

Ephemera shows that the Larkin organization could also be petty and demanding. A 1921 letter to the postmaster at Enosburg Falls, Vermont (Figure 6) is somewhat rudely critical of the postmaster because they returned a letter from Larkin to an addressee in Enosburg and did not state the reason for non-delivery. A penciled note shows that this was done two days later. Presumably, someone from Larkin was responsible for tracking non-deliveries and the reason for same. For example, if a prospective recipient had died, there would be no sense in sending them any more correspondence. There was no question as to their organizational and marketing efficiency.

The following year, another letter from Larkin (Figure 7) offers a financial incentive to the postmaster at Enosburg if they will provide Larkin with mailing lists. It’s very specific as to what they want and provides an interesting insight to Larkin’s target markets. Not quite a bribe…or is it? Abe Lincoln, where is your influence on Larkin integrity? Presumably still smarting from the implied criticism of the year before, and perhaps reluctant to sell address lists to Larkin, the Postmaster has noted on the letter in pencil “No one available”.

Was the business model already beginning to fray? Products could be promoted in the 1920s through the new medium of radio. Even larger entities such as Sears were selling products by mail, featuring price rather than premiums, and selling to individuals rather than local ‘Clubs’. The business model was being tweaked and when founder John Larkin died in 1926 the creative and adaptive force may have diminished. He would have had to devise how to compete with department stores and the impact of the automobile which let customers drive to the source of their products.

Later on, the Larkin organization would have had to compete with television’s Shopping Channel. And one can see some of the Larkin genes in the Internet’s new giant retailer, Amazon.

Business models evolve and change to reflect technological and social changes. And ephemera can remind us of the ongoing impact of American marketing ingenuity to adapt to those changes.