Colonial America Lotteries

In the United States today, lotteries are run by 46 jurisdictions: 43 states plus the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and (US) Virgin Islands. Hot Lotto. Decades of Dollars. Wild Card 2. 2by2. MegaHits. Tri-State. Mega Millions. Powerball . Win for Life. Pick 10. Mid-day Numbers. MatchPlay. The list is almost endless.

More Americans than ever before are playing lotteries, bringing in $56 billion in 2011 alone. Funds from these lotteries are earmarked to pay for education, environmental protection, senior citizen programs, juvenile detention facilities, and various public services. This is much-needed revenue that is not available from the multitude of income, property, estate and use taxes.

But U.S. lotteries are by no means recent phenomena. Lotteries in Colonial America were plentiful and an exceptionally effective method for the colonies to raise funds required for military payrolls, schools, bridges, street repairs, etc.

Massachusetts – The First Colonial Lottery

The first authorized lottery in Colonial America took place in Boston Massachusetts in 1745. Colonists had already been subjected to unusually high poll and estate taxes, but significant military debt, among other obligations, was still outstanding. On January 9, 1745, the General Court passed an act that provided for the payment of debt, “in a manner the least burdensome to the inhabitants,” that is, by a lottery.

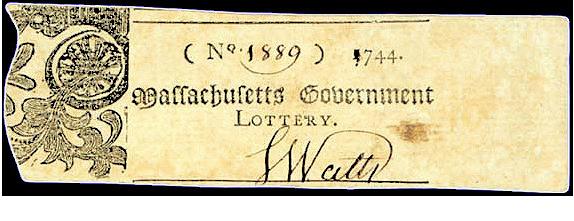

Illustrated here is a ticket from the first Massachusetts lottery. Notice that the year on the ticket is 1744, not 1745. The new year did not officially begin in Britain until the Incarnation of Christ which was celebrated on March 25th. Most individuals, institutions and even the newspapers had long recognized and used January 1st as the date on which the new year started, but legally it was not until 1752 that England officially adopted January 1st as the first day of the new year. As such, even though the lottery act was passed on January 9, 1745, tickets that were printed and sold over the next months had a date of “1744.”

Sheets of 25,000 tickets were printed in three segments. The left segment was called the “benefit” segment, that is, the piece of the ticket that was to be pooled with all possible winning segments and hopefully chosen as the winning (“benefit”) piece at the eventual lottery drawing.

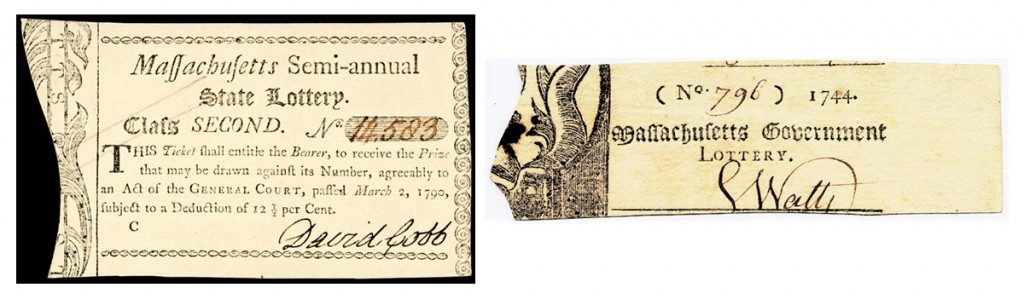

The center segment was the piece retained by the lottery official as a match to the purchased ticket. The right, larger segment was the actual ticket with the words “Massachusetts Government Lottery.” The tickets were numbered consecutively 1-25,000 with the left and center segments, or stubs, given the same number as the attached ticket. Of the 25,000 tickets, 5,422 were designated as “benefit” or winning tickets, a better than 1 out of five odds.

When a ticket was sold, one of the lottery directors signed the ticket and then cut it out along the left side of the design area and gave the ticket to the purchaser. This cut was purposefully curved and was called an “indent”, as seen in the below examples.

The idea was that each ticket would have a unique curve that would perfectly join the indent on the center segment of the ticket, the “stub” that the lottery director kept. The intent was to prevent counterfeiters from making false tickets or altering the number of a losing ticket.

Several days before the drawing, the left-side benefit segments were separated from the indented center stub pieces and placed into a strong box with five locks and seals. Benefit stubs from unsold tickets would also be placed in the box, thus accounting for all possible numbers between 1 and 25,000.

On the appointed day, the directors and administrators of the lottery would gather in a predetermined public meeting place and draw the winning numbers.

The process was to continue all day. If the lottery could not be completed in one day, the box was relocked and sealed and the drawings would continue on a succeeding day (except Sunday) until all the tickets had been announced.

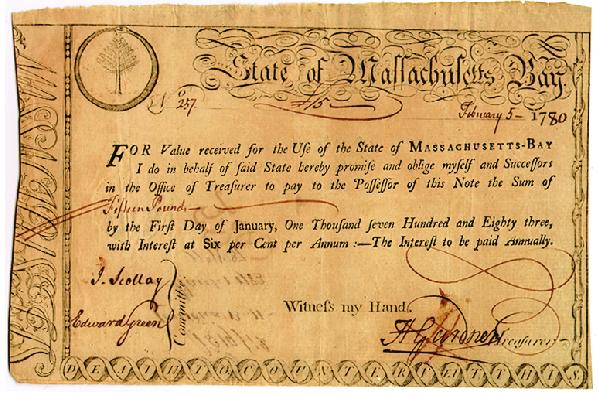

Once the winners had presented their tickets, they were to be paid within 40 days. Interestingly, 20% of the winnings was collected as a tax “for the use and service of this government.” Thus, the winners were only were given 80% of their winnings.

If for some reason, the colony needed to delay payment for a winning ticket, the winner would receive a “promise to pay” certificate, such as the one illustrated here, which could be redeemed at a later time with the addition of interest earned on the original winning amount.

By all accounts, the first colonial lottery in Massachusetts was a success. Thus, shortly thereafter, Rhode Island initiated their first lottery for the purpose of acquiring funds to build a bridge across the Weybosset River in Providence. Many other colonies followed suit and eventually 164 authorized colonial lotteries existed up to the outbreak of the Revolutionary War.

Rhode Island Lotteries

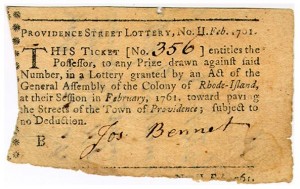

Rhode Island had the most lotteries with 82. Each lottery could have several “classes.” For example, on February 23, 1761, a petition to the Rhode Island General Assembly was received from several of the inhabitants of Providence requesting a lottery so that the profits could be used to pave the streets of that city.

The repair work was to be accomplished in three steps and, thus, three “classes” of lotteries. The proceeds of the first-class lottery would be used to pave from the bridge towards uptown as far as the money would allow. Proceeds from the second class lottery would be used to pave from the bridge downtown. Finally, there would be a third-class lottery to subsidize the paving from the bridge westward over Weybosset.

The lottery ticket illustrated here is from the second class of the Providence Street Lottery, No. II, February 1761.

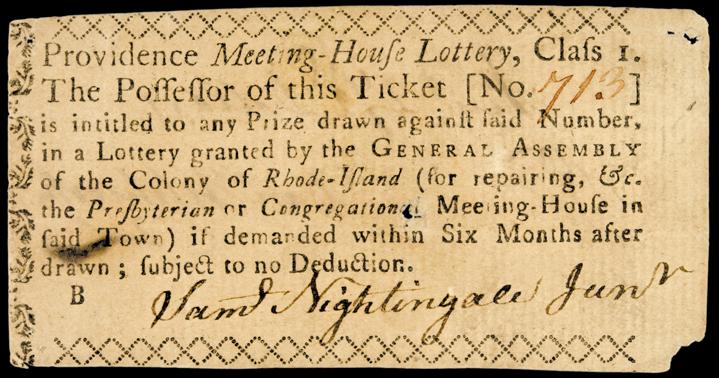

A scarce Rhode Island lottery ticket is the one below from the Providence Meeting House Lottery. The lottery’s stated purpose was “For Repairing etc. the Presbyterian or Congregational Meeting-House in Said Town.” It is a $2 1/2 Winning ticket, with the prize award amount and endorsement noted on its blank reverse.

Pennsylvania Lotteries

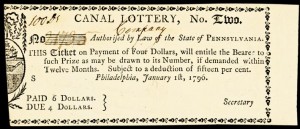

Some of the more ornately designed lottery tickets were produced by the various cities in the Pennsylvania colony. This is a January 1, 1796, “Canal Lottery, No. Two” ticket from Philadelphia.

It is not signed in the lower right-hand corner by “Secretary”, but rather states “Company” and is notated “100 Ds” (dollars), in the upper left-hand corner. This “company” tag and the $100 amount clearly indicates this was a winning ticket in the drawing to be paid to the agreed-upon “company” that purchased the ticket.

Continental Congress Lotteries – A Failure

The lottery trend continued quite actively throughout the Revolutionary War and the Confederation period. One of the most significant developments was the creation of “national” lotteries organized by the Continental Congress.

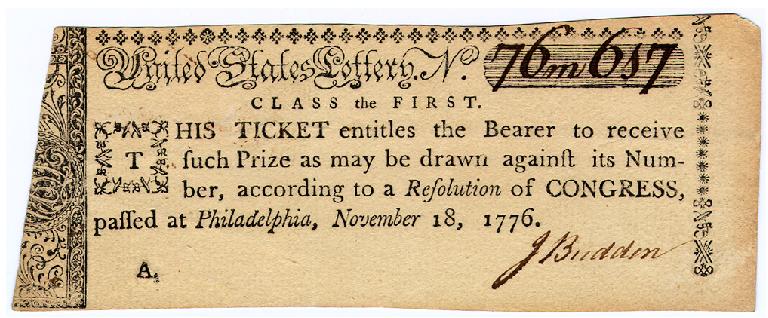

However, in stark contrast to the success lotteries found on the state and the local levels, the national lottery was a dismal failure. On November 18, 1776, the Continental Congress enacted a national lottery in four classes, consisting of 100,000 tickets in each class. From this seemingly well designed, elaborate lottery, It was calculated the Congress would obtain $1,500,000 from the four classes, a considerable amount of money in 1776.

A ticket from the First Class lottery is illustrated below.

Sales of tickets for the first-class lottery were far slower than expected, forcing the lottery officials to postpone the drawing several times. Distribution problems in selling and publicizing the lottery was a significant issue throughout the country.

Finally, on May 1, 1778, the drawing was begun with only 20,433 of the 100,000 tickets sold. When the final tickets were drawn on May 27th, about 36,500 of the $10 tickets had been sold. Of course, the government-owned the remaining tickets and is estimated to have ended up with a net loss of more than $72,000!

These losses continued with the other classes of the lotteries for a host of mismanagement reasons. But most importantly, the problem was compounded by the greatly depreciated value of the continental dollar during these years.

At the completion of the first class lottery in May of 1778, it took 2-5 Continental dollars to equal one dollar in actual exchange value. By the completion of the second class lottery in June of 1779, it took from 13-20 Continental dollars. By the completion of the drawing a year later, the rate of exchange was over $1,000 in Continental bills to $1 in actual exchange value.

The final calculation for the government’s winnings from the entire lottery was less than $100,000, a small fraction of the anticipated proceeds of $1,500,000.

For additional insight into the Colonial America lotteries and the failure of the Continental Congress lottery, see: John Samuel Ezell, Fortune’s Merry Wheel: The Lottery in America, Cambridge, MA: Harvard, 1960; and specifically on the Continental Congress lotteries, Lucius Wilmarding, “The United States Lottery,” The New York Historical Society Quarterly, 47 (1963) 5-39.