Following the Breadcrumbs . . .

I recently bought a card on eBay primarily because it showed a whale, and I collect 19th-century trade cards and letterheads which feature whale images. Once it arrived, I realized there must be an interesting story behind the image and the card.

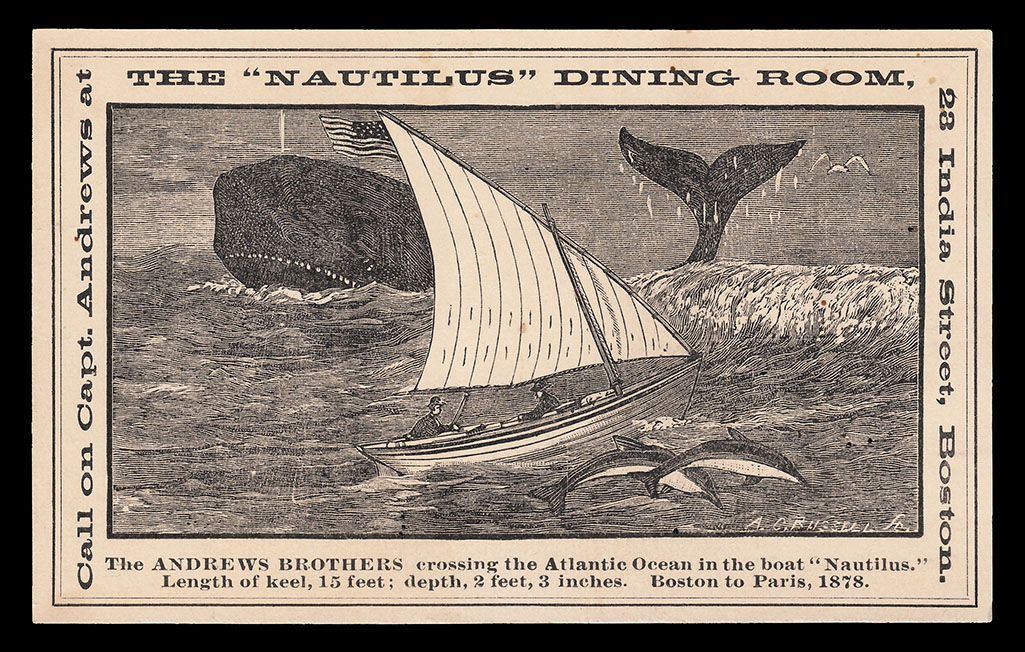

The card promotes the Nautilus Dining Room on India Street, close by the Boston waterfront. “Call on Capt. Andrews” at the restaurant, says the card, and notes that the image shows “The Andrews Brothers crossing the Atlantic Ocean on the boat “Nautilus.” Length of keel, 15 feet: depth 2 feet, 3 inches. Boston to Paris, 1878.” The image depicts the Nautilus mid-ocean, under sail near a huge whale. It turns out that this record-setting ocean crossing was an internationally celebrated event at the time. Whether this card was issued to attract folks to the restaurant in order to meet and greet the celebrated Captain William Andrews in person, or whether this dining room was operated by Andrews himself to capitalize on his fame, I have as yet been unable to establish. So far no account of his later activities mentions a restaurant.

In any event, therein hangs a tale. It begins the year before this Andrews brothers crossing of the Atlantic. A salty whaling hand named Thomas Crapo (age 35) of New Bedford, Massachusetts, on land after nearly two decades of whaling, was looking for something to do, ideally, something which would reverse his recent fortunes, after having unsuccessfully tried his hand as a fish mongerer. He found himself working as a laborer, but wanting much more out of life. He was well-aware of the 1876 crossing of the Atlantic in a small boat by a man named Alfred Johnson. A deeply experienced mariner, Crapo ordered built a 20-foot long, 13-foot wide two-masted boat made of cedar, purposely a bit smaller than Johnson’s, which he named the New Bedford. With tapered ends fore and aft, it looked much like a dory, but was built more like a whaling boat. With his wife Johanna (age 23, who insisted on going with him) he set sail to cross the Atlantic in the smallest boat known to have attempted it. Crapo had previously crossed the Atlantic some 21 times. He apparently would have much preferred to sail alone for fear that critics might say that he did it with help rather than alone, and so he forbid his wife from helping for much of the trip. In front of 3,000 well-wishers, the couple departed New Bedford on May 28, 1877. The boat promptly leaked and developed other problems, and he was forced to come ashore for repairs and improvements before setting out once again. They completed the crossing in 51 days. During their passage, Johanna (who had been to sea with him previously) did help out a bit a bit here and there. As their bed was to short for either of them, neither ever got much sleep.

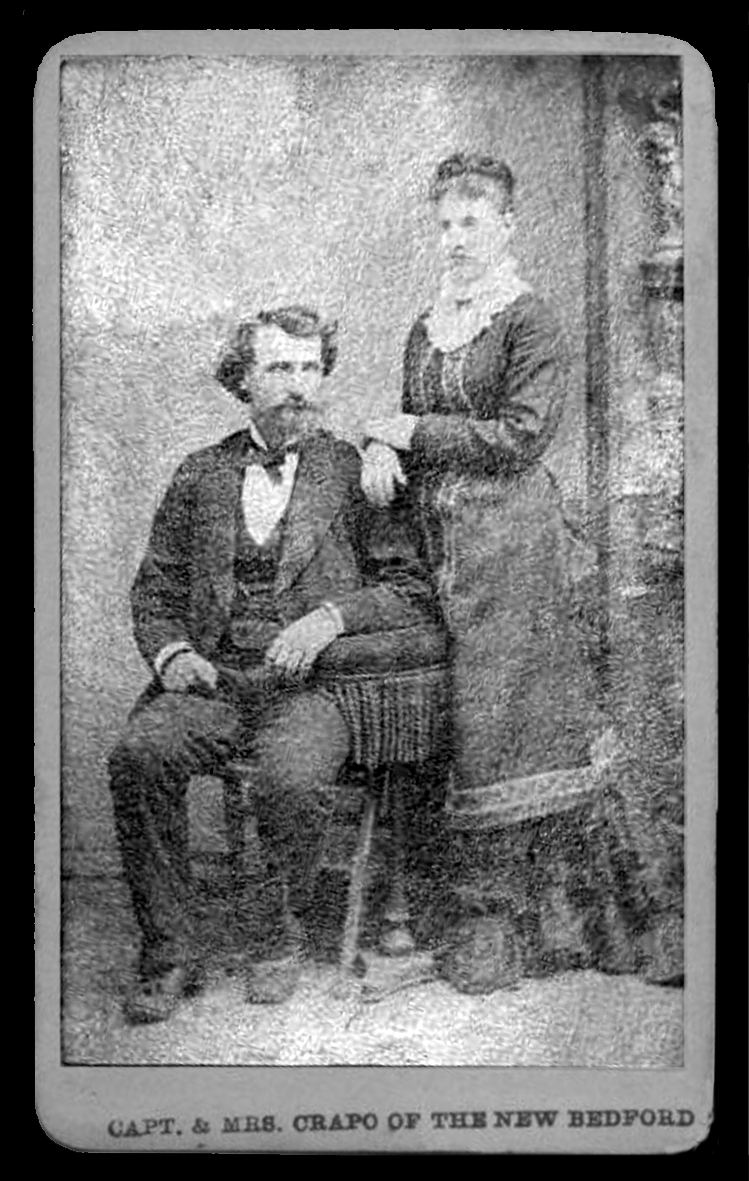

Captain & Mrs. Crapo

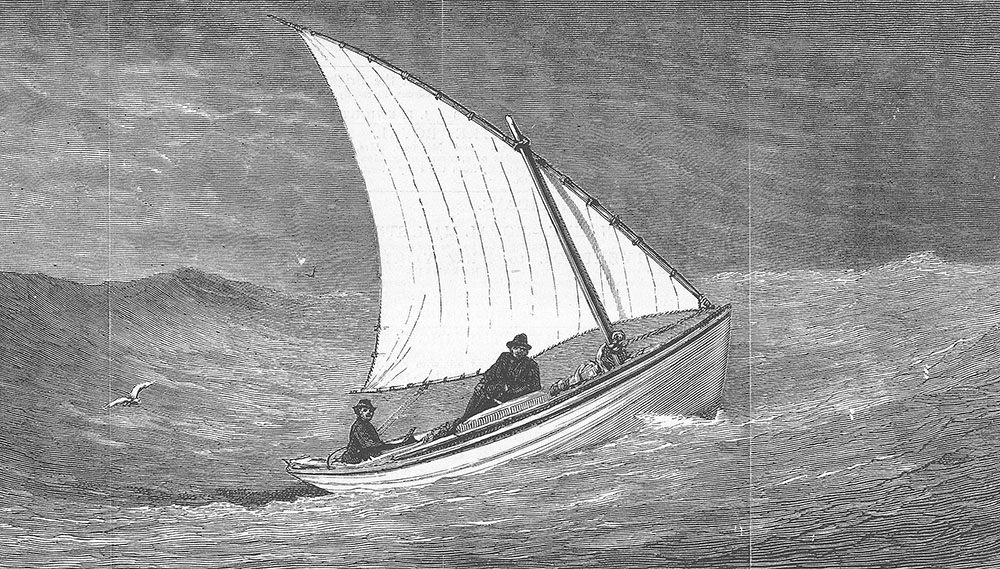

The Crapos enroute. A painting by Charles Raleigh, based on a sketch “done by the mate of the Cunard steamer Batavia, which passed the New Bedford. (Mystic Seaport Museum)

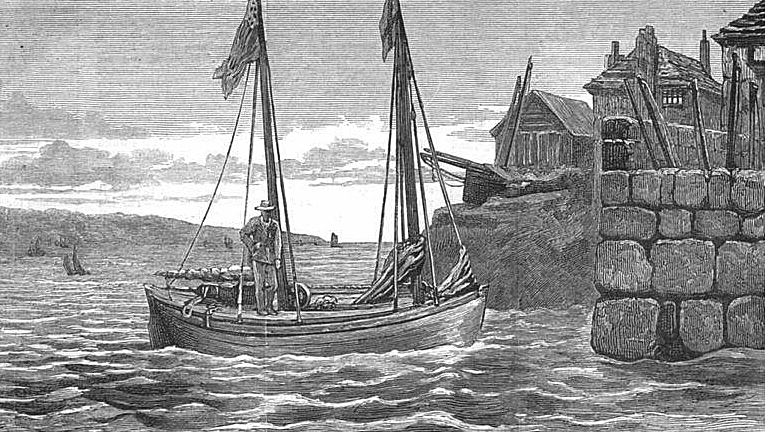

The New Bedford in Cornwall (The Graphic, London, August 4, 1877)

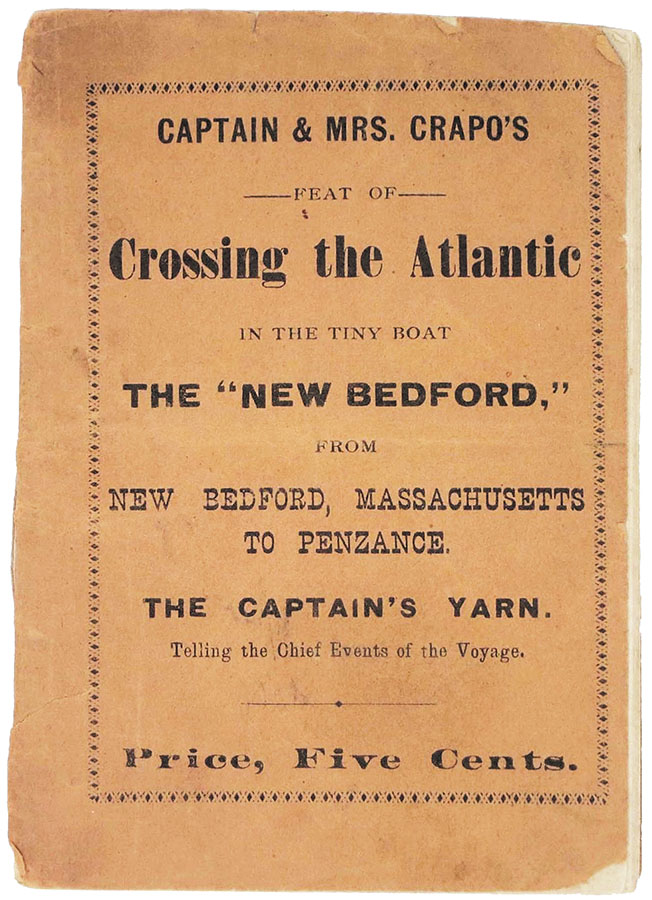

The Crapos were celebrated and feted across Europe for months and returned to receptions in Gilmore’s (later Madison Square) Garden and other places. They published an account of their passage, Captain & Mrs. Crapo’s Feat of Crossing the Atlantic in the tiny boat the “New Bedford” from New Bedford, Massachusetts to Penzance. They toured with a circus. Crapo had succeeded in acquiring the fame, excitement and increased income he had sought. He bought a coastal trade schooner, later trading up to a brig which used the New Bedford as its skiff. In 1898 that ship was lost, taking the New Bedford with it. Almost 60, Crapo again found himself down and out. He died in 1899 attempting to sail to Cuba from New Bedford in a 9-foot dinghy. Left penniless, his wife re-issued the story of their trip, with an introduction entitled Strange, But True, mentioning that sales of the booklet were her sole means of support.

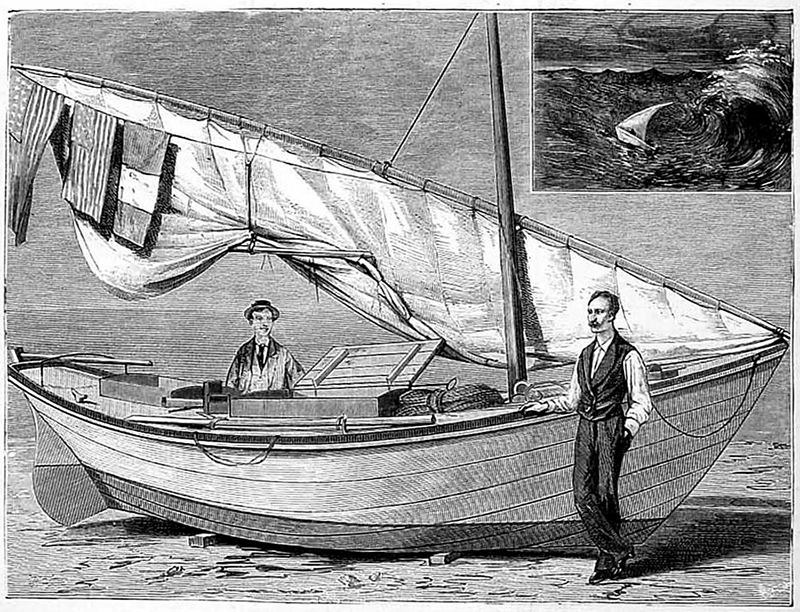

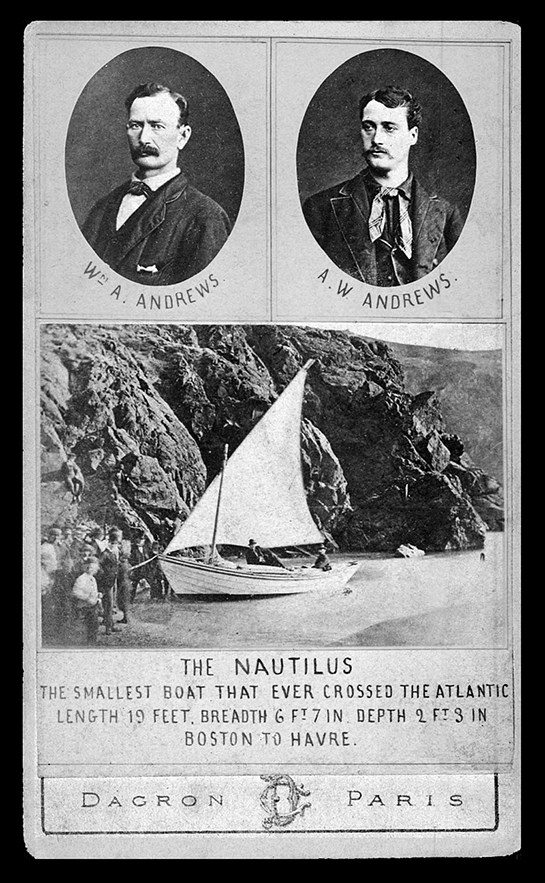

Enter the brothers Andrews, William (age 35, married with 3 children, pianoforte-maker for Chickering, wounded Civil War veteran) and Walter (age 23, single). In the Fall of 1877, at the height of the Crapo’s fame, they were idling one afternoon on the cliffs overlooking Beverly harbor, which was filled with ships and dories. On the spur of the moment, they decided themselves to cross the Atlantic “in one of these dories” (from their subsequent book, A Daring Voyage Across the Atlantic Ocean, E.P. Dutton, NY 1880), shook hands on it, and had built their own custom lapstreaked cedar dory, one that was shorter than Crapo’s. Their 19-foot craft, the Nautilus, made by Higgins and Gifford of Gloucester, actually measured only fifteen feet along its keel. It was much narrower (only 6’ 7” wide), less deep ( 2’ 3”) and much lighter than Crapo’s. Nautilus, carrying one triangular sail, was fully decked with two hatches, one at the rear for the helmsman and one forward for entry into the tiny, cramped space below. The wood on the deck and sides of the boat was thin, a mere 1/2 inch thick. A French report later dubbed the craft “a cockle-shell”.

This periodical wood engraving of the Nautilus is clearly the source for my trade card image, in which a huge whale and some porpoises near the boat were added. (The Graphic, London, Vol. XVIII, August 24, 1878)

At the outset, William knew neither how to sail nor navigate, having been to sea only once, as a passenger. Younger brother Walter had spent a lot of time on boats. William (William Albert) and Walter (Asa Walter) left Boston harbor on June 7, 1878, from Coyne’s Wharf on City Point, on their 3,000-mile journey. Like the New Bedford before it, the Nautilus was forced immediately to return ashore for repairs before setting out again. They made it to Cornwall, England on July 31, and following another stop sailed into the harbor at Le Havre, Paris. Their crossing took but 45 days, thus achieving their goal of bettering the Crapo crossing. In his 1880 book, William reports that “the smallest vessel ever in Havre from America before the Nautilus was a schooner of 213 tons. The weight of the Nautilus is 600 lbs.”

The Nautilus on European shores. (The Illustrated Sporting & Dramatic News, London, October 26, 1878)

Later analysis revealed that their amateur navigation had taken them along an amazingly straight course, overall.

Their crossing was miserable, though their daily log nearly always sounded optimistic. They and all their belongings—including beds —were soaked with water throughout the entire trip. At times they did not sleep for a week. They suffered fourteen gales. More than once they were put in serious danger by pods of whales which at times they could reach out and touch. Some of the whales used the Nautilus to scratch their backs. Any of those whales could have sunk them in a split-second either on purpose, playfully or accidentally. When threatened by whale activity, William said he went below and closed his eyes, putting them out of his mind. His ostrich-head-in-the-sand approach worked out in the end.

A carte de visite celebrating the Andrews brothers’ accomplishment.

Their arrival in Paris occasioned a two-day celebration through streets festooned with bunting, and brightly lit public spaces at night. The brothers slept in feather beds. The Nautilus was put on display at the 1878 Paris Exposition until it ended on November 10th, then put on display in London and other English cities. The dory was put on a Cunard liner along with Captain Andrews (the ill Walter having returned to the USA earlier). William worked on the liner to pay for his return passage.

During their crossing, Walter had hemorrhaged blood a number of times. Shortly after his return to the United States, he died. Captain William in 1892 sailed an even smaller 14’ 6” cedar and canvas boat from Atlantic City to Palos, Spain. He then wrote a second book, about that second voyage.