Fire! Victorian Advertisers Capitalize on Danger

Nineteenth-century advertisers had no need to sensationalize the dangers of fire; its threat was ever-present. Homes were heated and meals cooked on wood, coal and gas-fueled stoves. In the evening, families gathered by the light of oil or gas-burning lamps, portable versions of which were carried upstairs to light the family to bed.

In cities, a fire could spread rapidly through adjacent buildings, particularly wooden ones. Massive fires that destroyed landmarks, entire blocks, and even neighborhoods were not uncommon. These conflagrations caused huge economic and personal loss.

Famous Fires

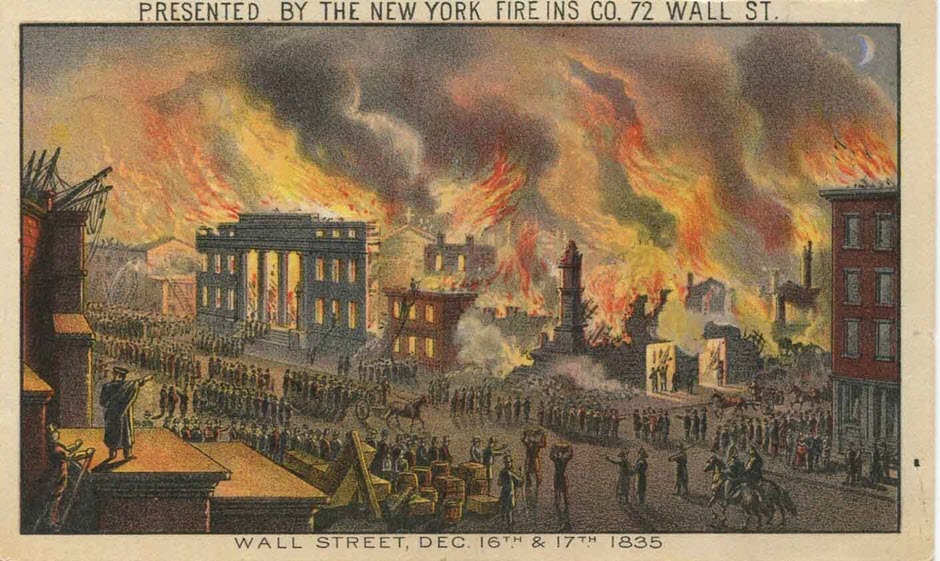

The “Great Fire” of 1835 started in a warehouse and went on to destroy nearly 700 buildings in New York City, leveling Wall Street completely. The City had only a volunteer fire fighting force at the time and the fire died out only when it reached the East River. In the aftermath, 23 of the city’s 26 insurance companies went out of business. The New York Fire Insurance Company, chartered in 1832, must have been one of the ones that survived. This 1880s-era trade card illustrates the disaster and includes the firm’s founding date on the reverse. Perhaps that was all the recommendation needed.

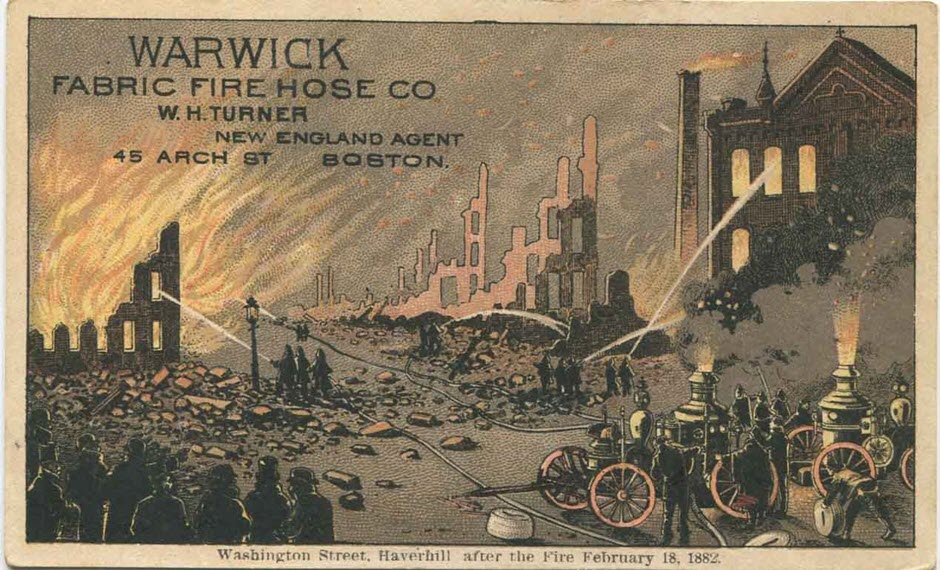

In 1882, a fire destroyed 82 shoe and leather firms in the town of Haverhill, Massachusetts, putting more than 2,000 people out of work. Early responders might have been more successful at halting the fire had one of their hoses not burst. The Warwick Fabric Fire Hose Company used a dramatic image of firefighters dousing the last of the flames amidst the ruins of Washington Street to advertise “The Most Perfect Fire Hose Yet Invented.”

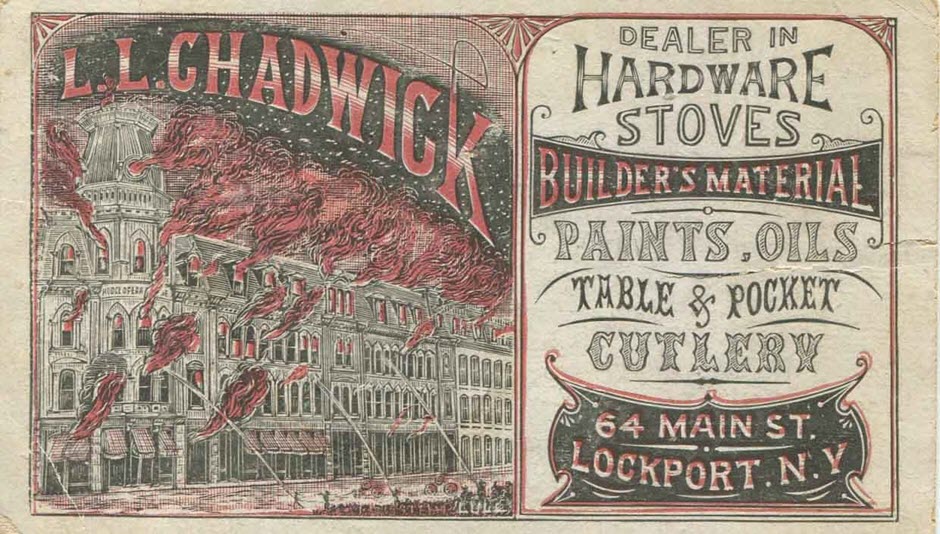

The Hodge Opera House was the “Pride of Lockport”, NY when it was built in 1871. Ten years later, it burnt to the ground. L. L. Chadwick, an enterprising purveyor of builder’s materials and home goods used the image of the burning opera house to advertise that he had everything needed to furnish a new (or re-built!) home.

Means of Escape

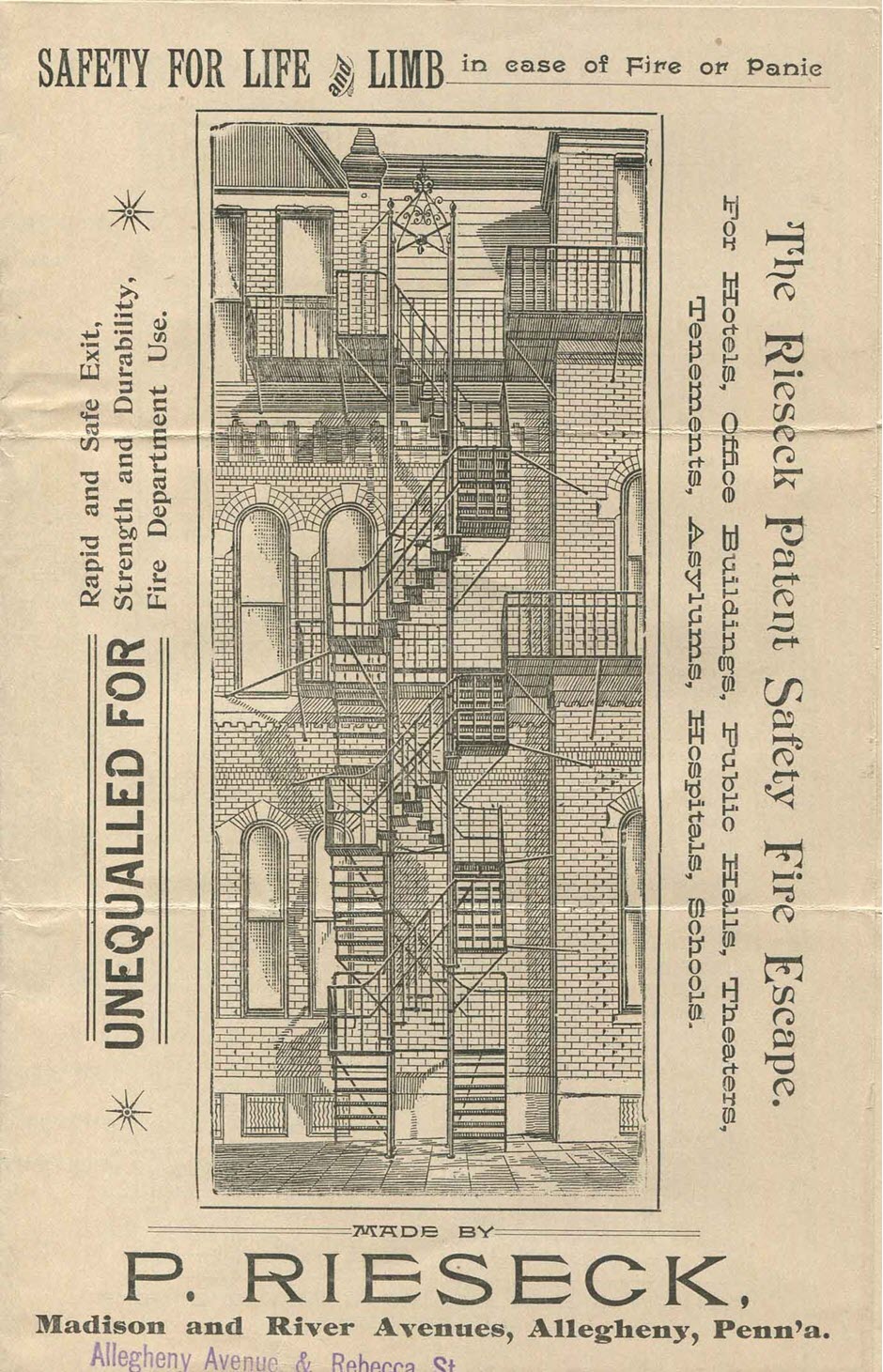

On June 3, 1885, Pennsylvania adopted a Fire Escape Law, mandating a “permanent, safe external means of escape” from all buildings over three stories in height. Structural Ironworkers, P. Reisdick, published the full text of that law and its supplement in this 1890s/1910s folder advertising their Patent Safety Fire Escape.

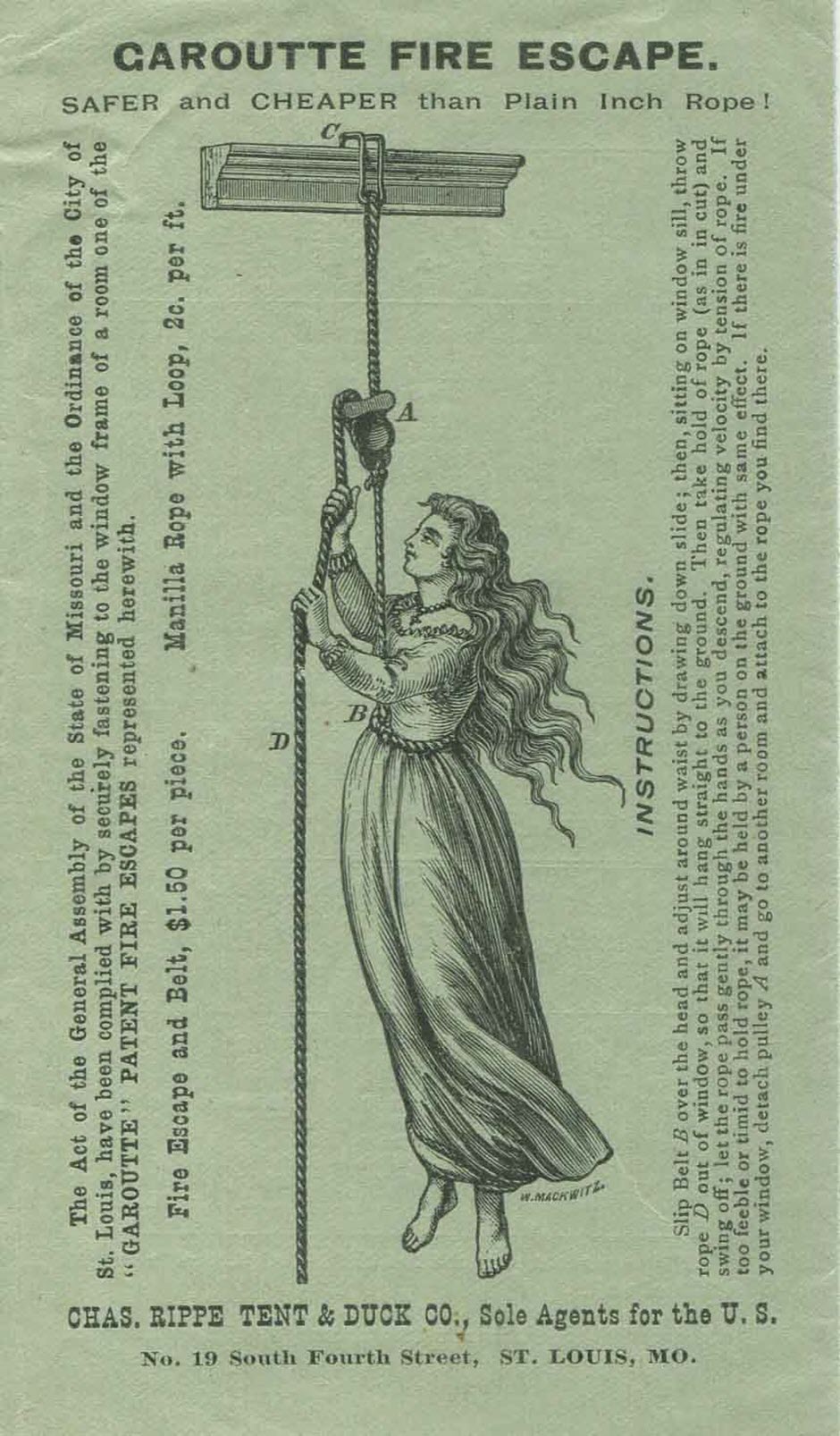

The Garoutte Fire Escape supposedly complies with a St. Louis, Missouri fire ordinance. It is at least “safer and cheaper than plain inch rope.” The instructions advise, “If there is fire under your window, detach pulley A and go to another room…” Sage advice.

Protecting Yourself and your Property

Nineteenth-century innovators developed a number of products that deterred fire or touted fire-protective properties.

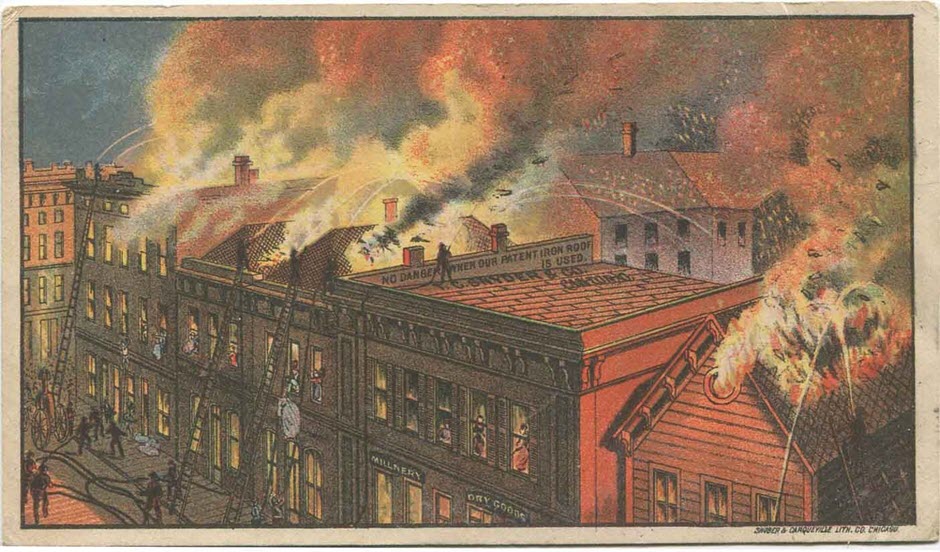

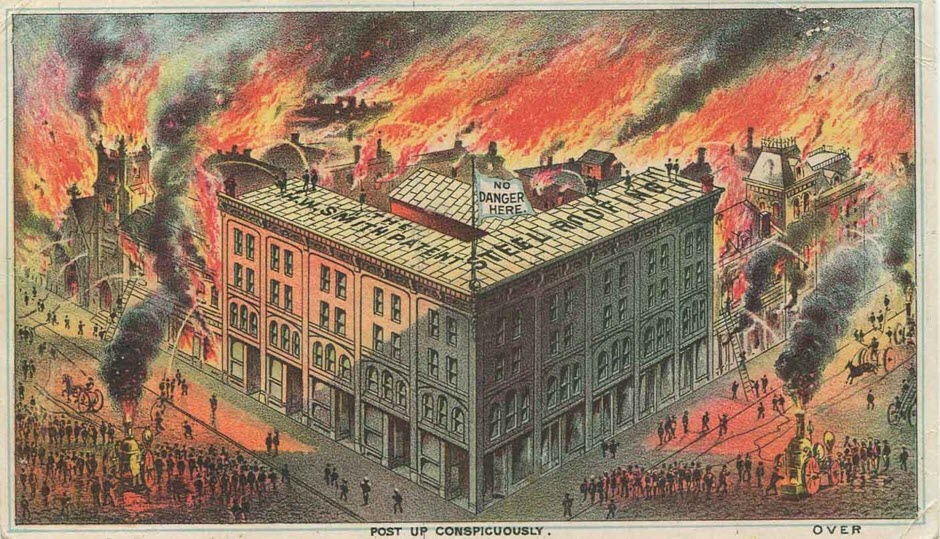

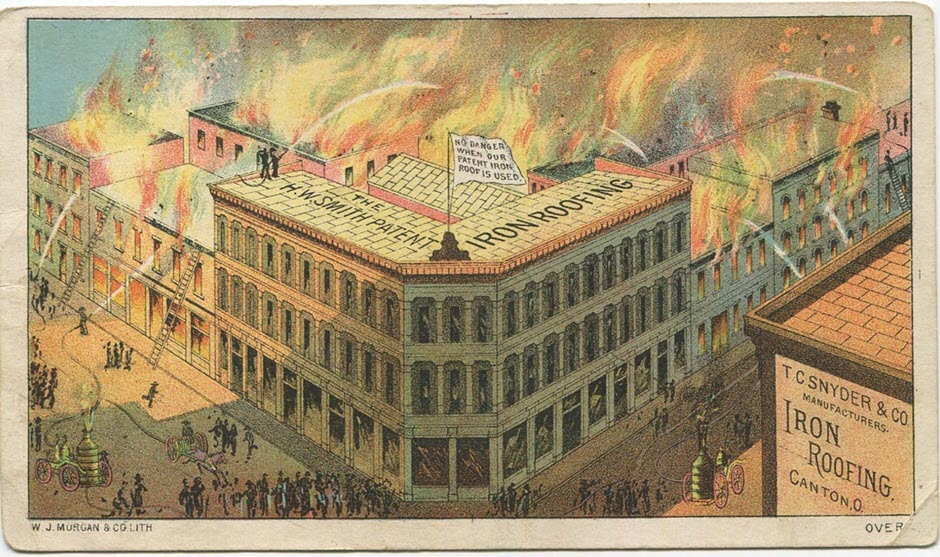

Steel or Iron Roofing was advertised as “fire-proof.” It was an enormous improvement over wood roofing and was adopted widely in the latter 19th century. W.H.T.C. Snyder & Co. issued a series of dramatic trade cards showing urban conflagrations; buildings with the Smith Patent Iron or Steel Roof remain un-touched while flames engulf the rest of the block.

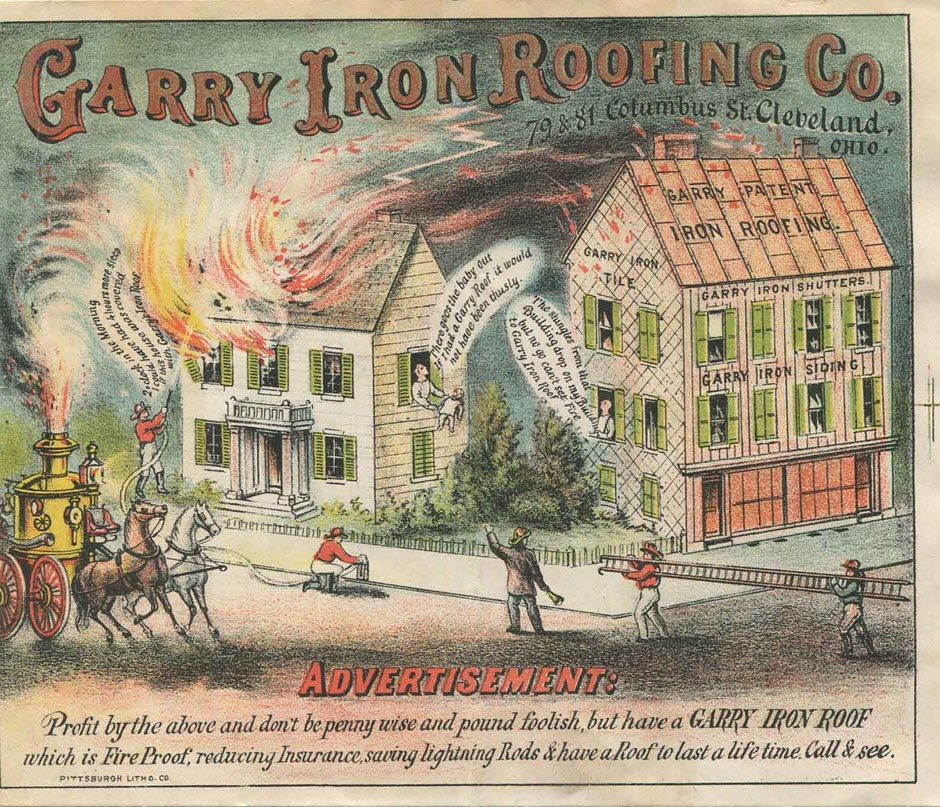

The Garry Iron Roof Co. fabricated roofing, siding, and shutters made of iron. The occupant of the house sheathed in those materials isn’t worried about burning shingles hitting his home, while the firefighter operating the hose complains that he could have had four hours more sleep if the house on the left had been covered with Garry’s Iron Roofing. All this while the unfortunate mother is compelled to toss her baby out the window!

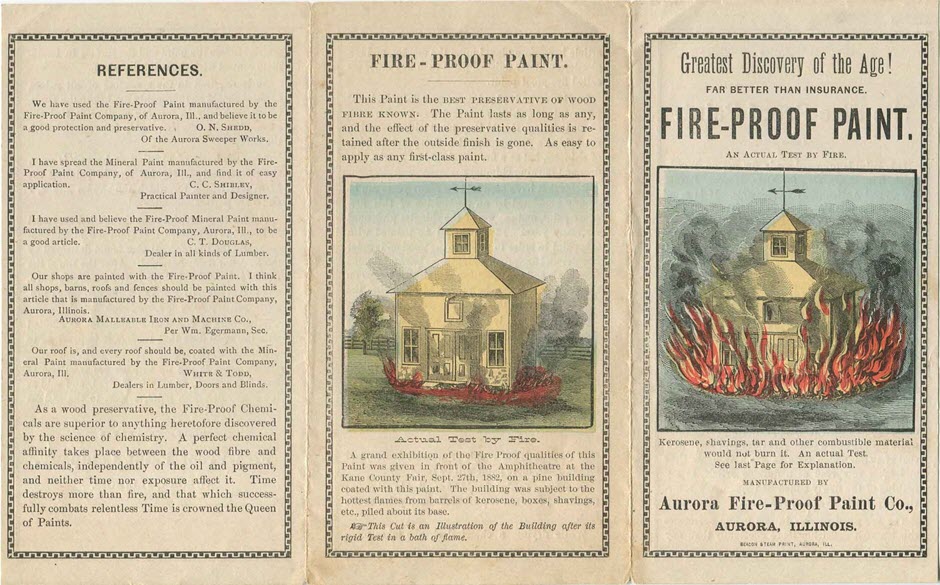

In this flier, the Aurora Fire-Proof Paint Company calls their product, “the greatest discovery of the age!” and “far better than insurance.” It is composed of “the best linseed oil and metallic bodies by an improved chemical process which renders it impervious to fire…” Fire-retardant paints and coatings are available today. Most of us are familiar with the foam-like finish of intumescent paint on structural steel. Today’s paints are categorized as “fire-retardant” or “fire-resistant” – never, “fire-proof.” It is unclear how Aurora’s paint actually performed, but the inclusion of “metallic bodies” must have been intended to mimic the protective qualities of the iron roof. The “Actual Test by Fire,” said to have taken place at the Kane County Fair on September 27th, 1882 is illustrated with a beautiful wood engraving showing the pine building sitting un-touched on a bed of flames. The cover image illustrates the dramatic alternative.

The mother and children fleeing their burning house for the neighbor whose house is coated with Lowe’s Metallic Paint are assured that she will be safe there, despite the flames licking the side of the house. Notice the children playing at the windows and the lady of the house calmly rocking on her porch.

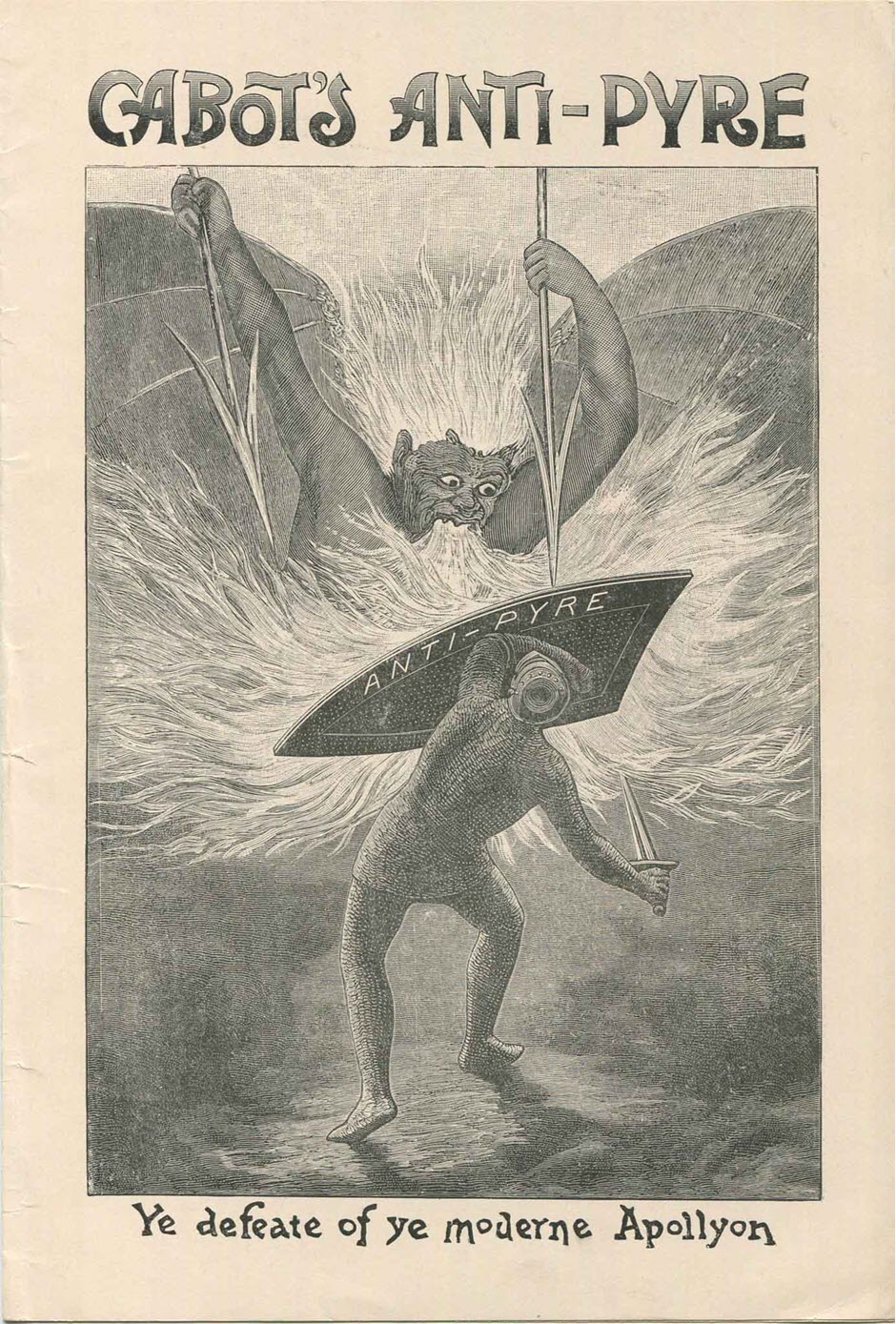

This folder for Cabot’s Anti-pyre takes an allegorical approach. Their product defeats the “modern Apollyon,” or “Destroyer” – Fire, embodied by a winged demon with flaming hair and breath. The product is a liquid fire-proofing and “the first and only protection against fire that is cheap.”

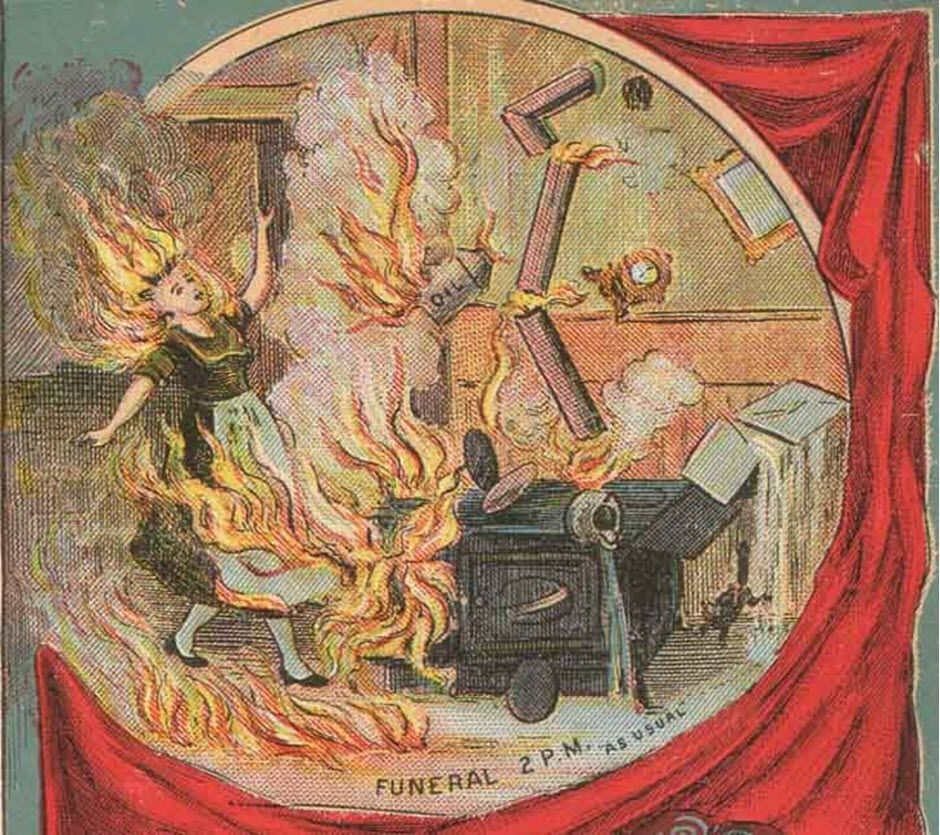

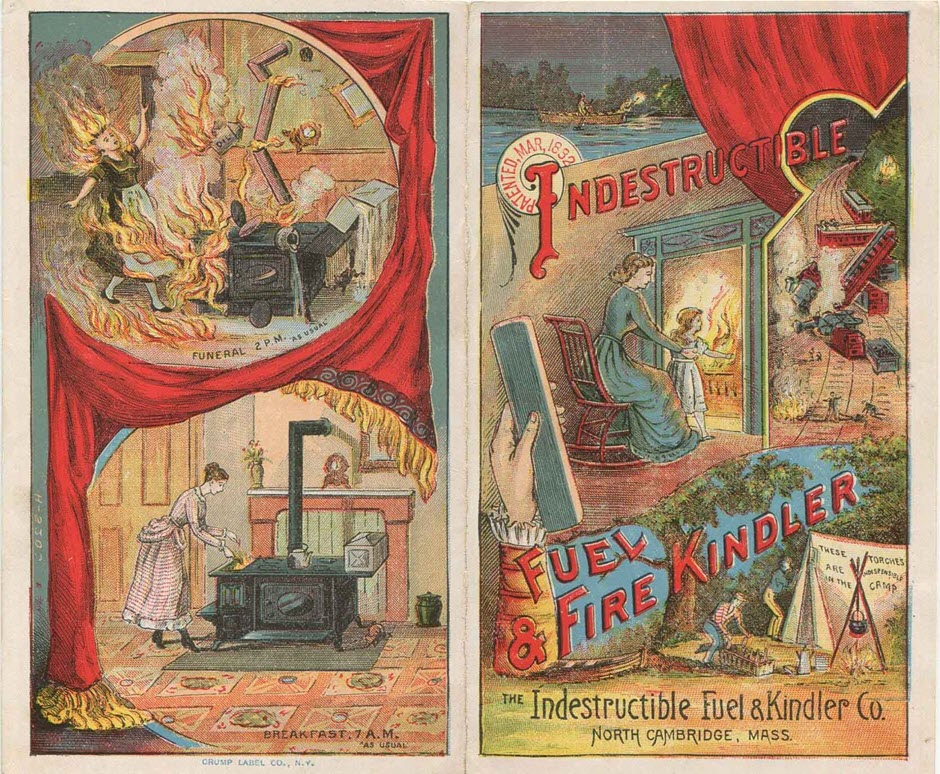

One of the most dangerous moments in keeping one’s grate, stove or lamp going was when lighting the fire. Highly combustible kerosene oil could burst into flame suddenly with disastrous results. Advertisers showed little restraint in illustrating these accidents. In a terrifying two panels, the Indestructible Fuel & Fire Kindler Co. shows how the use of their product will yield “Breakfast 7 AM as usual” while the flaming alternative results in “Funeral 2 PM as usual.”

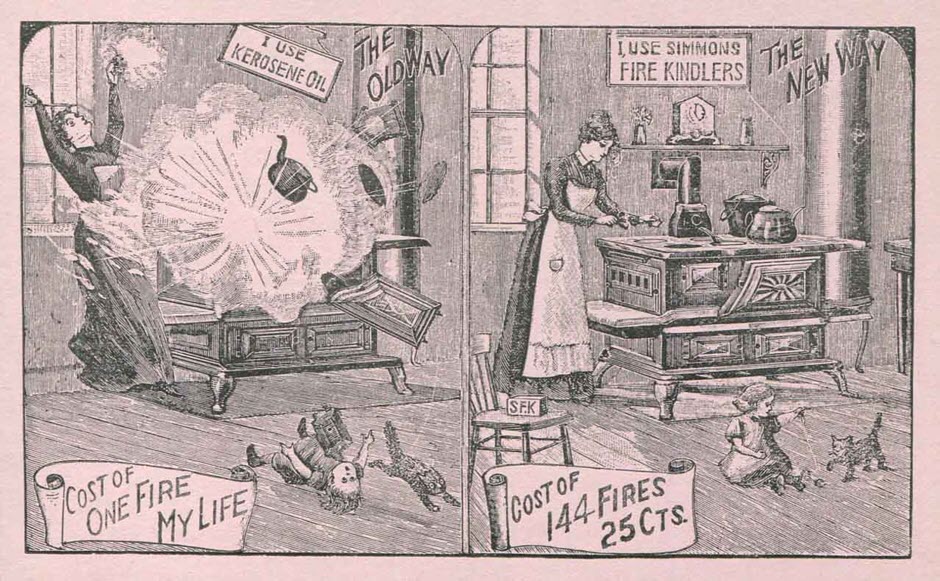

This trade card for Simmons Fire Kindlers adds a child playing in the kitchen for additional drama and compares the cost of one fire with the cost of 144 kindlers. Who can argue with spending 25 cents for fire kindlers to spare the life of a mother?

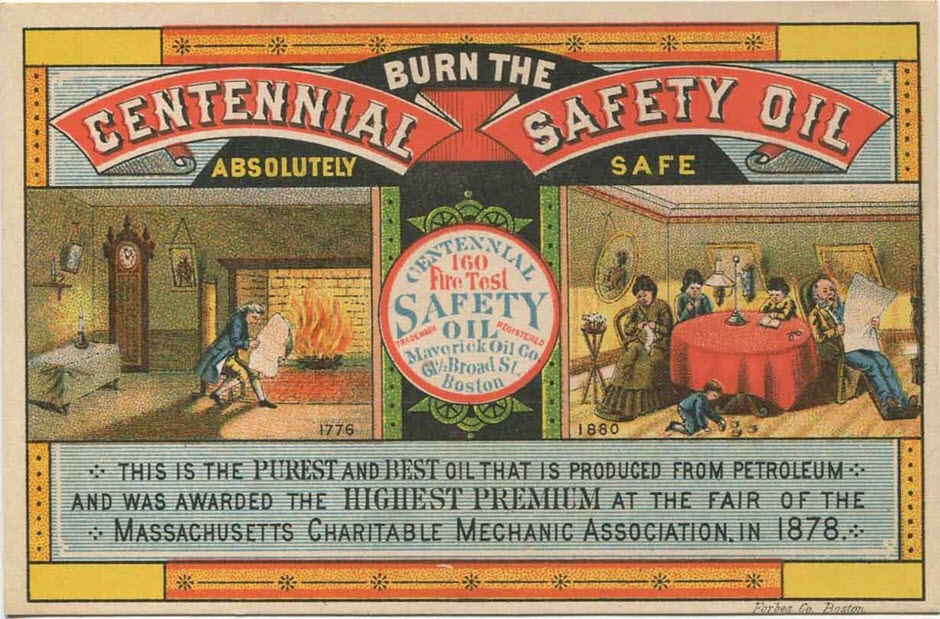

Some oil companies sought to improve their image for home use. This brand of petroleum oil has the word “safety” in its name. Nothing on this card explains exactly what makes Centennial Safety Oil “absolutely safe.”

With some home fires inevitable, fighting the fire was the next step. The Patent Fire Extinguisher worn on the back is described as “A Portable, Self-Acting Fire Engine.”

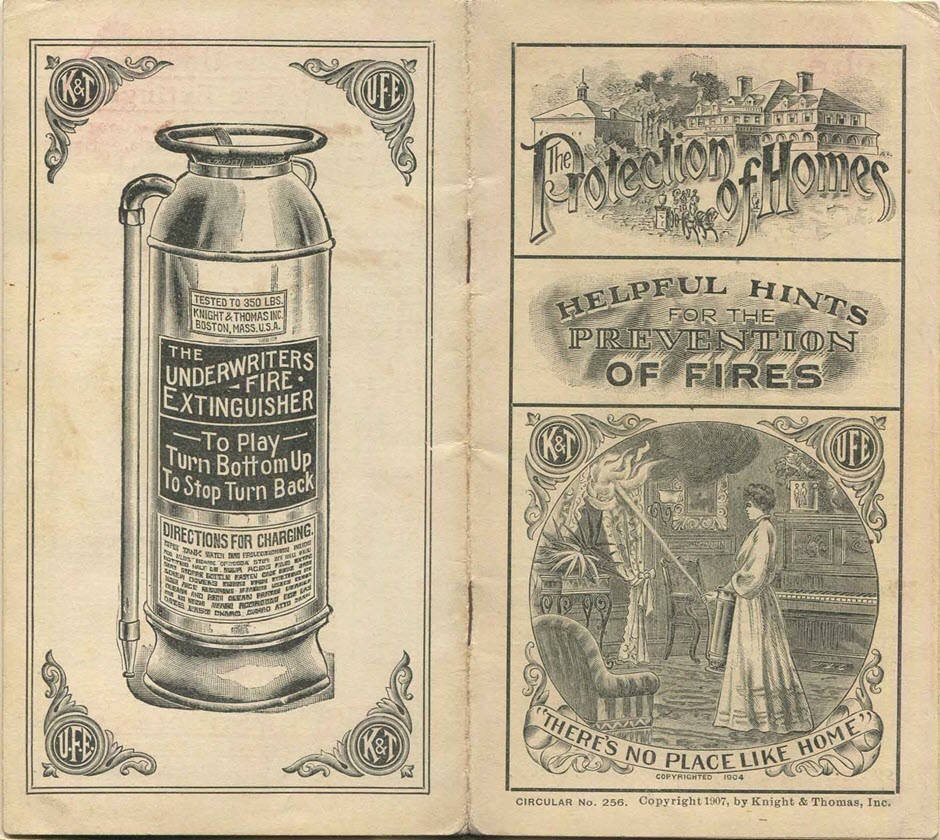

Knight & Thomas, maker of the Underwriter Fire Extinguisher, put out this booklet of “Helpful Hints for the Prevention of Fires” in the first decade of the 20th century. It lists a host of dangers including furnaces, chimney flues, lamps, gas stoves, and Christmas trees. An interior illustration shows a cook using the fire extinguisher on a burning stove. “Because of the carelessness of servants,” the company recommends keeping a fire extinguisher in or adjacent to kitchens. On the cover, the lady of the house calmly douses the drapes.

If the fire was out of control, it was time to hook up a hose – and probably summon the fire department. Hose manufacturers also exploited potential customers’ fears to sell their products.

Fabricators of the Safety Mill Hose warned those in the market to thoroughly investigate their product as “you won’t have much time for this subject when your property is on fire.”

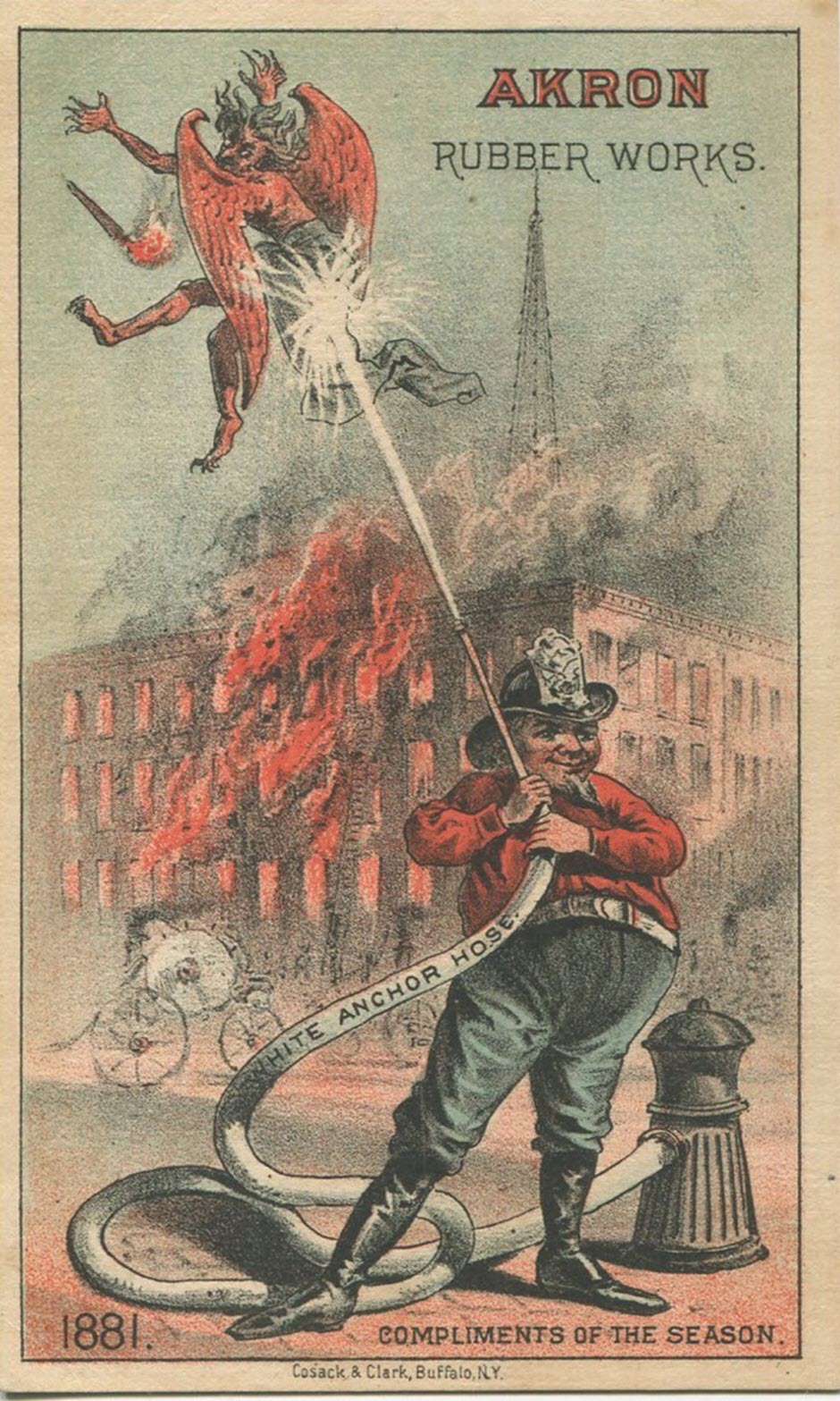

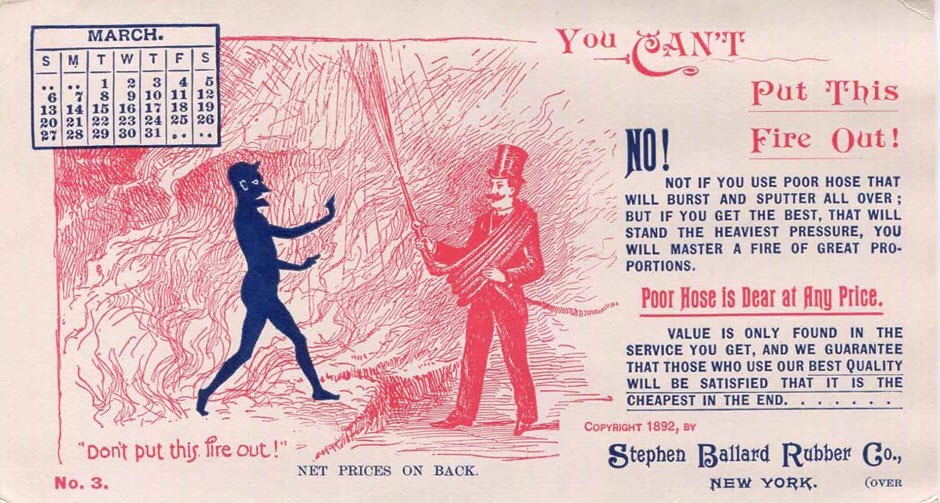

The Stephen Ballard Rubber Co. knows that you can’t put a fire out “if you use a poor hose that will burst and sputter all over,” but the demon protecting this fire is no match for their hose, wielded by a dashing gentleman in a top hat.

The Akron Rubber Works issued a series of new year’s cards featuring their White Anchor Hose. Whimsical rather than commercial in tone, this one features a jolly fireman startling a winged demon into dropping his flaming torch. The building engulfed in flames in the background is an odd touch for “Compliments of the Season.”