Colorful Circus Paper Traces the Spread of ‘Jumbomania’

Despite its featherweight, printed paper from the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art exerted enough power back in the 1880s to ignite and sustain enthusiastic public interest in a beloved 13,000-pound curiosity named Jumbo.

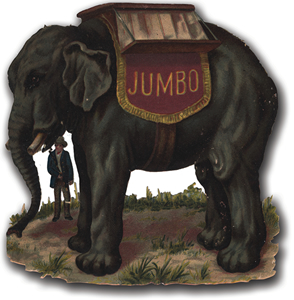

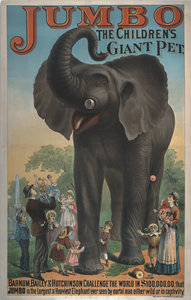

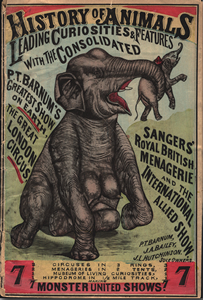

Circus paper encompasses a wide range of material such as tickets, letterhead, route cards, programs, lithographs, window cards, heralds and couriers that promote the upcoming season and highlight the star attraction. From 1882 to 1885, Jumbo was the attraction that captivated America in the realm of the circus and also in advertising.

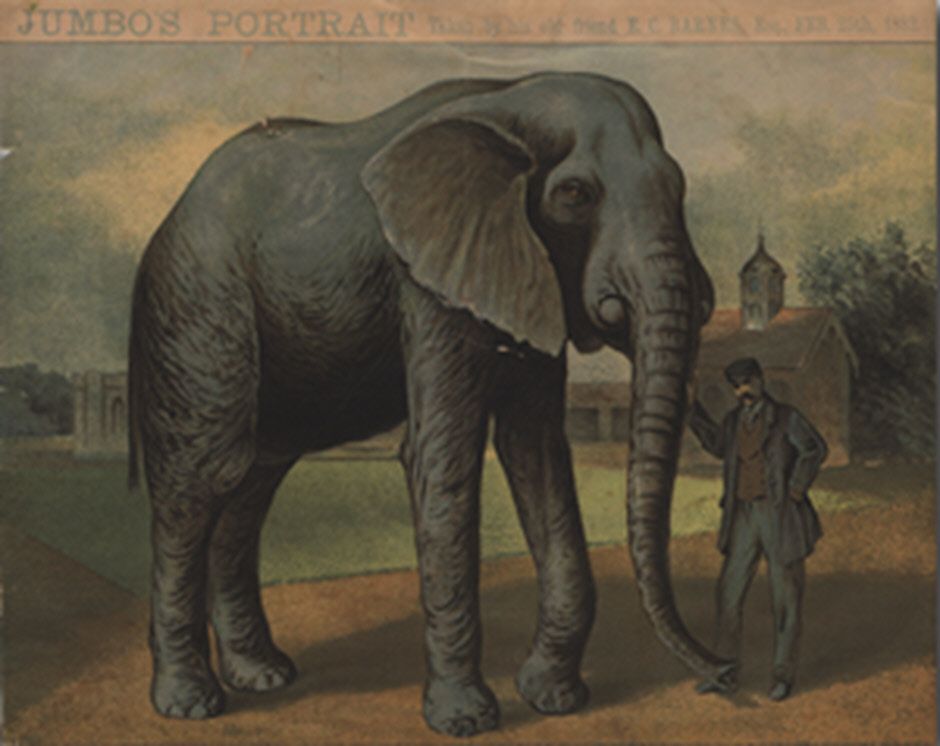

In 1861, Jumbo was born in sub-Saharan Africa, captured, taken to Cairo, and sold to a zoo in Paris. Because the Paris zoo had too many elephants in 1865, he was traded to London’s Zoological Gardens for a rhinoceros. The small, sickly elephant showed little potential for either international fame or national controversy. But, under the careful attention of his keeper, Matthew Scott, the elephant grew to the enormous height of 11 feet and weight of 6 1/2 tons. His trunk was 27 inches in circumference. In short, he was the biggest elephant known.

London zookeepers named the great elephant Jumbo, which might have been derived from a Swahili word for “hello” or “chief,” or from an African word for “elephant.” In addition to his great size, Jumbo had a gentle nature and gave thousands of children rides at the Zoological Gardens becoming the zoo’s star attraction. But Jumbo’s size and age worried Zoo officials who feared he might become dangerous.

One of Jumbo’s ardent admirers was American, P.T. Barnum (1810 – 1891). A spectacular showman and entrepreneur, Barnum was always searching for the extraordinary of any size. Barnum wanted Jumbo and offered $10,000 to the London Zoological Society for the giant elephant. The offer was accepted, but after the sale was announced, the English populace, from commoners to the Queen herself, protested.

Crowds descended on the Zoo to see Jumbo. The English press took up the cause, legal proceedings started and even Jumbo refused to leave the zoo. Barnum relished the free advertising. He clearly understood the influence of the press and the power of advertising. Just before his death, he wrote, jumbo

I am indebted to the press of the United States for almost every dollar which I possess… The very great popularity which I have attained both at home and abroad I ascribe almost entirely to the liberal and persistent use of the public journals of this country.

In February 1882, Barnum received a telegram from the editor of the London Daily Telegraph asking what it would take to cancel the sale. Barnum responded, “Hundred thousand pounds would be no inducement to cancel purchase.”2 With no other means to stop the purchase, Jumbo and his trainer sailed from England on the freighter Assyrian Monarch. The ship arrived in America on April 8, 1882. Once in New York City, Jumbo was transported to Madison Square Gardens in a special wagon that needed sixteen horses and the assistance of several circus elephants. He was greeted by thousands of spectators.

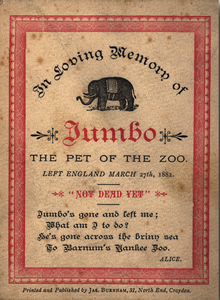

The Jumbo craze took hold on both sides of the Atlantic and all types of Jumbo memorabilia were created. A memorial card from Jumbo’s “wife,” another elephant at the Zoological Gardens, reads, “Jumbo’s gone and left me; What am I to do? He’s gone across the briny sea/ To Barnum’s Yankee Zoo.” Advertisers in America appreciated the commercial possibilities of the largest known elephant. The impact of Jumbo on advertising can be seen in trade cards from all types of companies that quickly jumped upon the Jumbo craze — from baking powder, oysters, suspenders, cleaning agents, photography studios, fasteners, boots, clothiers, sewing machines, and patent medicine to cotton thread. A Willimantic Thread Company trade card showed Jumbo being dragged towards America with the caption, “Jumbo Must Go, because drawn by Willimantic Thread!” The Hartford Sewing Machine proudly proclaimed, “This is ‘Jumbo,’ but the biggest thing out this season is the Hartford Sewing Machine.”

Traveling in a specially constructed railroad car, Jumbo became the prize attraction of the circus. His image was heavily advertised by the show in heralds and posters and he was seen by millions of people as he traveled around the country with the circus. Jumbo was a huge success, but unfortunately, the success was to be short-lived.

After the evening performance on September 15, 1885, in St. Thomas, Ontario, Jumbo and the other elephants were led from the circus lot to the train along the main line. An unscheduled freight train appeared in the distance. With a steep embankment on one side and the circus train on the other, Matthew Scott was unable to get Jumbo to safety and the mighty mammoth was killed. Shortly after the tragic event, Barnum circulated the story that the great elephant had turned back heroically to save Tom Thumb, a young elephant, from the locomotive. More than 100 years later, a 40-ton statue was erected in St. Thomas to commemorate the event and, in a Barnum-like move, to attract visitors.

Even in death, Jumbo provided new attractions for the circus. Years before, Barnum had contacted a taxidermist, Professor Henry A. Ward of Ward’s National Science Establishment in Rochester, NY concerning procedures that should be taken in the event of Jumbo’s death. Three days after the accident, the New York Times recorded that Ward and two other taxidermists removed the hide and bones.3 The rest of the body was cremated. Even that event drew thousands of spectators. Over the next six months, Ward and three assistants created not one but two Jumbos for the following circus season — a skeleton and a hide.4 When told that the hide could be made larger than Jumbo was in life, Barnum readily agreed.5

In 1886, both the skeleton and hide trooped with the circus; however, the two were never placed side by side in the tent because of their difference in size. In January 1886, Barnum acquired the elephant, Alice, from the London Zoological Garden. Alice arrived in time for the 1886 season and was billed as Jumbo’s grieving widow traveling with Jumbo’s skeleton and hide. To the circus owners’ delight, this bizarre attraction received a great deal of attention from the circus visitor and press. The New York Times reported, “Jumbo Stuffed a Greater Attraction than Jumbo Alive.”6 In the winter of 1889 – 1890, Barnum returned to England with his circus for the last time, and bought with him Jumbo’s skeleton and hide. Jumbo had returned to England.

Jumbo’s skeleton and hide were finally retired from trooping with the circus when Jumbo was replaced by the newest circus attraction, Barnum’s Sacred White Elephant. Barnum, who was a trustee of Tufts University, donated the stuffed hide to the University, where it was displayed until April 16, 1975, when a fire destroyed it. The skeleton was donated to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City where it was displayed until 1975. In 1993, the skeleton was again exhibited for the 100th anniversary of the founding of the American circus. The Museum’s press release read, “Jumbomania Returns to New York City” and, once again as in life and death, Jumbo drew appreciative crowds.7

Footnotes

A. H. Saxon, A. H., ed. Selected Letters of P. T. Barnum (New York: Columbia University Press, 1983), 334.

Ibid, 223.

New York Times, September 18, 1885, p1.

New York Dispatch, February 28, 1886. Barnum, Cole, Hutchinson & Cooper Scrapbook, 1886. The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art collection.

Flint, Richard W. “Jumbo Recycled,” Bandwagon, vol. 23, n0. 4, July – August 1979, p. 17.

New York Times, March 23, 1886. Barnum, Cole, Hutchinson & Cooper Scrapbook, 1886. The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art collection.

Office of Public Affairs. Press Release, “Jumbomania Returns to New York City” American Museum of Natural History, January 1993.

About the Authors

Deborah Walk, Curator of the Circus and Historical Documents

Jennifer Lemmer, Collections Manager for the Tibbals Collection

Marcy Murray, Curatorial Assistant

The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art

FSU/Ringling Center for the Cultural Arts

Florida State University

Sarasota, Florida

Open to the public, the Ringling Museum is comprised of an Art Museum founded by John and Mable Ringling, a historic home the winter residence of the Ringlings and a Circus Museum celebrating the history of the American circus.

Selected Bibliography

Adams, Bluford. E Pluribus Barnum: The Great Showman and the Making of U.S. Popular Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

Barnum, P. T. The Life of P.T. Barnum, Written by Himself. New York: Redfield, 1855. Life of P.T. Barnum Written by Himself. Brought up to 1886. Buffalo: The Courier Company, 1886.

Barnum, P.T. Struggles and Triumphs; or, Forty Years’ Recollections of P.T. Barnum. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981; abridgement of 1869 edition: NY: American News Company, 1871.

Kunhardt, Jr., Philip B., Kunhardt III, Philip B. and Peter W. Kunhardt. P. T. Barnum: America’s Greatest Showman. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995.

Saxon, A. H. P. T. Barnum: The Legend and the Man. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989.

Saxon, A. H., ed. Selected Letters of P. T. Barnum. New York: Columbia University Press, 1983.